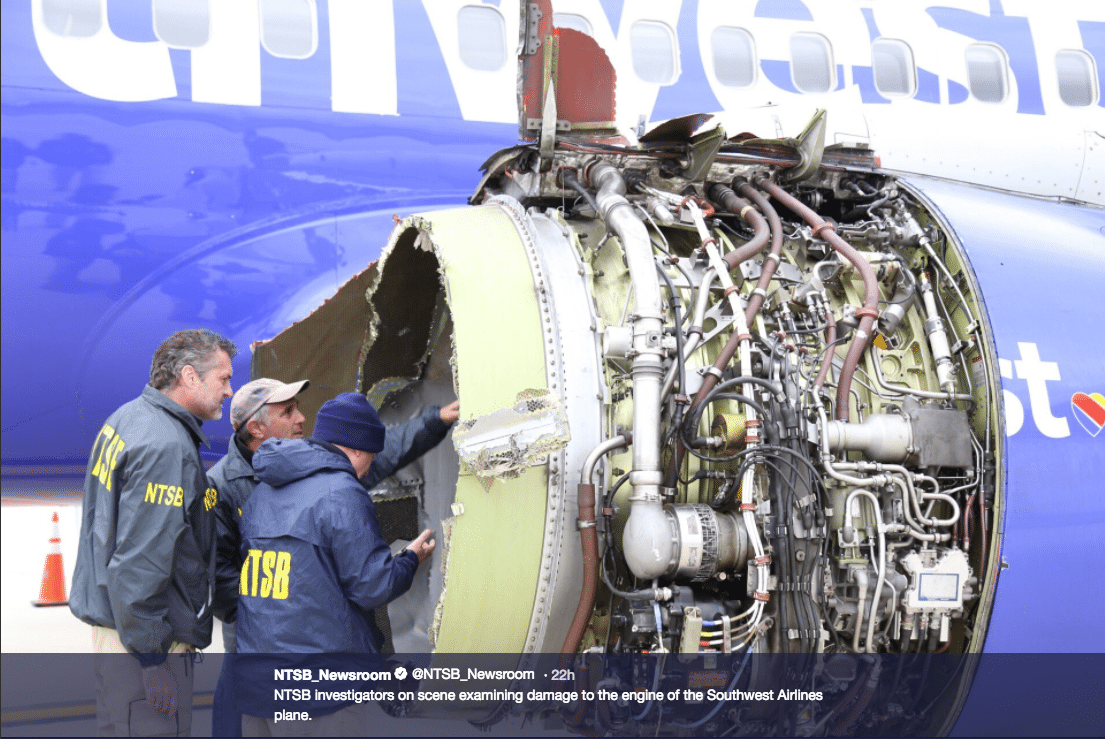

NTSB Investigators examining the CFM56 engine of Southwest Flight 1380. Photo courtesy of the NTSB

On a given day, Boeing 737-family aircraft take flight thousands of times. Of those planes, 706 are members of the Southwest Airlines fleet. While most go without complication, Tuesday’s Southwest Flight 1380 was not that lucky.

About 20 minutes into the scheduled flight from New York to Dallas, the 737-700 suffered a major malfunction to its left engine, one of two CFM56-7Bs supplied by CFM International. In the words of pilot Tammie Jo Schults, whose icy-cool audio has captured the internet’s attention, the aircraft was “not on fire, but part of it’s missing.” With the help of ATC, the former U.S. Navy F/A-18 pilot diverted to an emergency landing in Philadelphia.

Of the 149 people on board, 148 survived.

Unfortunately, one passenger was sucked through a shattered window and later died. The passenger — Wells Fargo executive Jennifer Riordan, according to CNN — was seated on the same side as the failed engine and was pulled through the window after an object broke through it. Passengers said they managed to pull her back into the plane after several minutes, but she succumbed to her injuries.

Besides Riordan, seven of the 144 passengers were injured.

Despite reports that the fatality broke a nine-year spell without one on a U.S. airline, the Independent Pilots Association said that a UPS Airlines crash in August 2013 resulted in the death of two crewmembers.

NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt said in his first briefing regarding Southwest Flight 1380 that the engine showed “signs of metal fatigue.” He also mentioned an airworthiness directive for CFM-56 engines and the desire to see whether additional scrutiny is required.

In a second briefing, Sumwalt provided reporters with more information that the investigators captured from reviewing the aircraft’s flight data recorder (FDR).

“As the aircraft was climbing through about 32,500 feet, the engine parameters, both RPM indicators on the left engine went down to zero, oil pressure went down to zero, and the engine vibration increased significantly on the left engine,” he said.

Shortly thereafter, the cabin altitude warning horn was activated, indicating that the cabin altitude was “going down to about 14,000 feet,” said Sumwalt. The aircraft then began an uncommanded left roll at about 41 degrees of bank angle, compared to the normal 20 to 25 degrees of bank that is typical when flying a commercial airliner, such as the 737, according to Sumwalt.

Sumwalt said the FDR information indicated that the flight crew elected to land with flaps five, as opposed to the normal setting of flaps 30 or flaps 40, which the pilots used because they were concerned of aircraft controllability issues. The speed at touch down was around 165 kt, compared to a typical 737 approach speed of around 135 kt, according to Sumwalt, who is a former 737 pilot.

NTSB is still collecting debris from the engine that fell to the ground in areas around Philadelphia as the airplane was approaching to land.

Southwest has said that it is assisting the NTSB and the FAA. It also said that it is accelerating its existing engine inspection program relating to the CFM56 engine family,” which it expects to complete in the next 30 days. Sumwalt said that Southwest’s measures would involve ultrasonic inspection on the entire fleet.

Engine-maker CFM International (a 50/50 joint venture of GE and Safran Aircraft Engines) and jet-supplier Boeing both released statements in which they also expressed condolences and pledged to assist the NTSB in its investigation.