Uber has held fast to its plan to be in the air by 2020 and off the ground by 2023. (Uber)

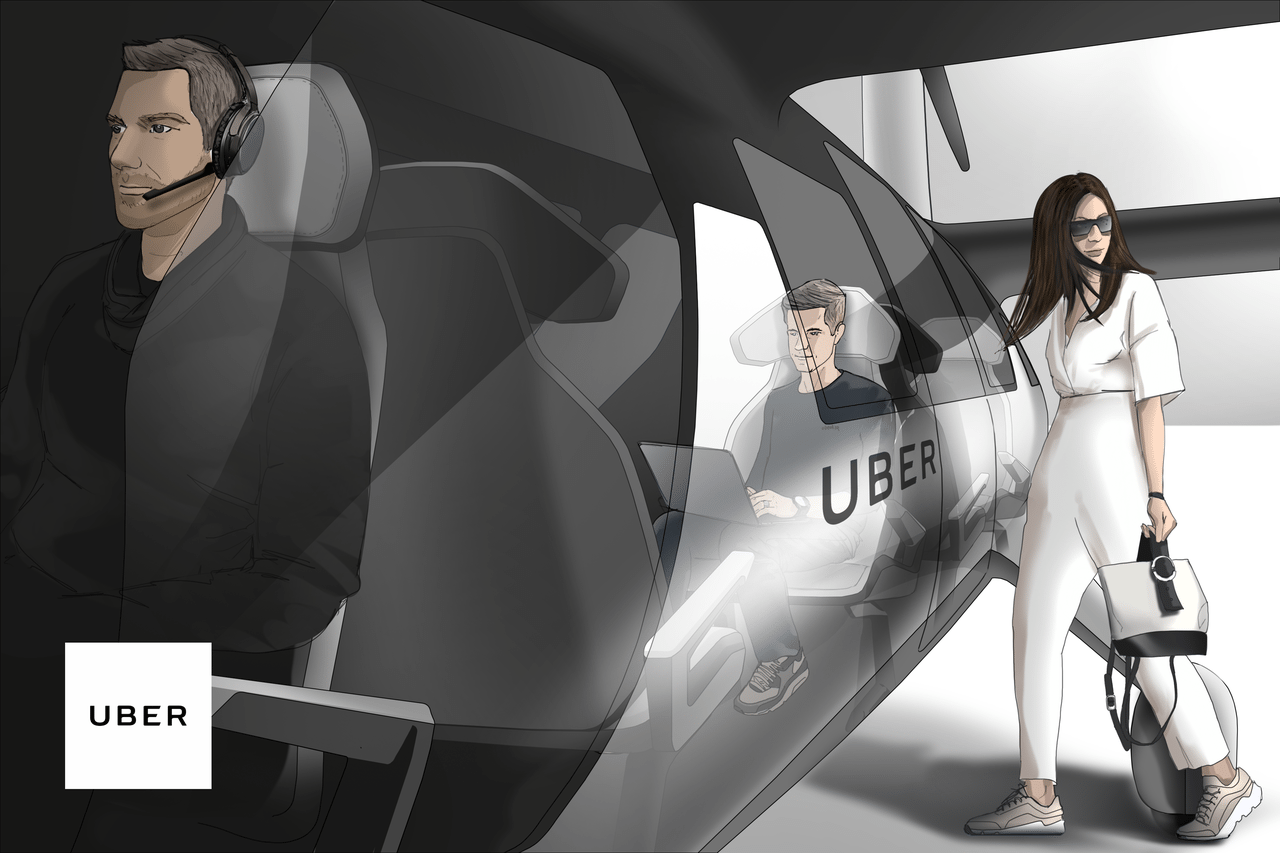

With Uber’s second annual Elevate Summit came big promises. The ridesharing giant’s plan for a network of electric vertical-takeoff-and-landing (eVTOL) aircraft to ease frustrating ground traffic in urban areas was unheard of just two years ago.

Uber and its various industry partners have unveiled concepts for what that aircraft, its vertiports, its batteries and other aspects of the plan might look like at its May summit in Los Angeles. Uber said it wants to begin urban air taxi operations in Dallas and Los Angeles by 2023, with testing to begin in 2020.

Uber aims to perform at least 400 and up to 1,000 takeoffs and landings per hour to and from its vertiports once operational. That’s one takeoff or landing at least every 10 seconds.

For that frequency of operation to be successful, several assumptions in the business plan related to scaling production and utilization of the aircraft are required.

“This will require a new pathway to regulation and acceptance by the public,” said Michael Thacker, Bell’s EVP of technology and innovation. Bell has partnered with Uber to develop an air taxi. The helicopter manufacturer unveiled its concept air taxi cabin at January’s Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas.

Most of the vertiport designs shown by Uber’s partners have little in common with current heliports. Several of the designs incorporated tall buildings, with layers of landing pads on both sides of the heliport. After landing, the electric air taxis would be moved by conveyor belts to loading areas while simultaneously being recharged and from there to a departure pad.

A rendering of an Uber vertiport. (Uber)

The approach raises some questions, like whether an eVTOL aircraft can safely land on the downwind side of a building with other air taxis generating turbulence above and beside it. With rotorcraft approaching the vertiport from all directions, even with the aid of ADS-B and other advanced technologies, could this level of movement be conducted safely?

Each Uber vertiport would require up to six megawatts of power. According to Nancy Sutley, chief sustainability officer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, that much power would require an individual circuit from the nearest sub-station. Furthermore, the permits and actual construction time for the required infrastructure are considerable. As Sutley said, “You better start now.”

Autonomy also is a big part of Uber Elevate’s plan. Human pilots would operate Uber’s air taxis at the inception of the program, but the company plans to move to semi-autonomous and then full-autonomous control of the vehicle when the technology matures.

In a four-seated air taxi, vacating the pilot’s seat increases productivity by 25% (sic), Uber said. Robotic ground vehicles have trouble navigating cluttered city streets and complex terrain, but Uber officials believe autonomous flight is more easily and safely accomplished in the relatively obstacle-free air above cities.

A simulator for Bell’s air taxi concept. It has four seats and simulates autonomous flight. (Bell)

Up there, Uber’s air taxis would not have to contend with or avoid obstructions like road construction. Still, backlash to the fatal accident of a self-driving automobile has colored discussion of autonomous air taxi service.

Certification of the aircraft presents yet another question for the air vehicles. Due to their simplistic design, Uber said its electric air taxis should be certified under Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) Part 23 governing light aircraft rather than FAR Part 27, which regulates helicopters up to an altitude of 7,000 ft.

In Uber’s 2016 white paper, the company argued that certification should occur under a standard put forth by ASTM International Committee F44 on General Aviation Aircraft. The committee develops and maintains standards crafted as acceptable means of compliance for general aviation aircraft rules and regulations globally. Its standards are consensus-based where the “community takes responsibility for developing the certification basis and then presents it for adoption by the regulator.” Uber points to ASTM’s F37 committee that proposed the regulation for light sport aircraft as an example of how its eVTOL should be certified.

Uber makes a point that there are no regulations for heliports. This is true — the FAA has always used advisory circulars to suggest standards for heliports, thus avoiding the messy proposition of actually going through the rulemaking process. Individual states are responsible for heliport criteria, but in general, the states adopt the advisory circular as the standard. Thus the FAA gets its standards implemented without the rulemaking process. Uber sees this as a way to gain a consensus-based standard for its vertiports. In its view, this would simplify the process and would allow Uber more latitude in its design of vertiports.

An issue Uber’s plan does not address is pilot availability. Uber’s projections on the number of pilots it would need to accomplish its goals have not been well defined. John Langford, president and CEO of Aurora Flight Services (now owned by Boeing), noted at the summit that the number of commercial pilots in the U.S. has steadily fallen since 1974.

FAA data shows that the number of commercial helicopter pilots has not varied significantly from a total 15,000 since 2008. Reading into Uber’s utilization rates, it conservatively would need 1,000 pilots to provide air taxi service in a single city.

That would require one out of every 15 commercial helicopter pilots flying today to fly eVTOLs for Uber. Uber does “anticipate that demonstrating successful operation with early vehicles would reduce the requirements for pilot experience in conventional aircraft based on reduced pilot task loading.”

Uber said there already is precedent for this. “A multi-engine rating can be achieved in far less time if it is limited to centerline thrust (one engine in front and one in back) rather than conventional twin-engine aircraft where an engine failure presents an asymmetric thrust condition that can be quite challenging to manage,” Uber said. Basically, Uber believes the criteria for a FAR Part 135 pilot would be reduced from its current standards when flying an eVTOL.

In Uber’s white paper, the company also projects a pilot’s annual salary, fully burdened, at $50,000. Taking 25% as the cost of employee benefits means the pilot would see less than $40,000. But 25% in employee benefits does not allow for any training costs. According to Salary.com’s 2018 survey, only 10% of helicopter pilots in the U.S. make below $65,000 per year.

Neither during the two days of Uber Elevate’s Summit nor in its 97-page white paper are maintenance personnel mentioned. One portion of the white paper indicates that there would be a need for maintenance at a facility other than the vertiport. The paper, however, does not address a maintenance personnel shortage projected for the industry.

Uber is currently seeking by July 1 interested governments to participate as Uber’s international launch city.

This was originally published by Rotor & Wing International.