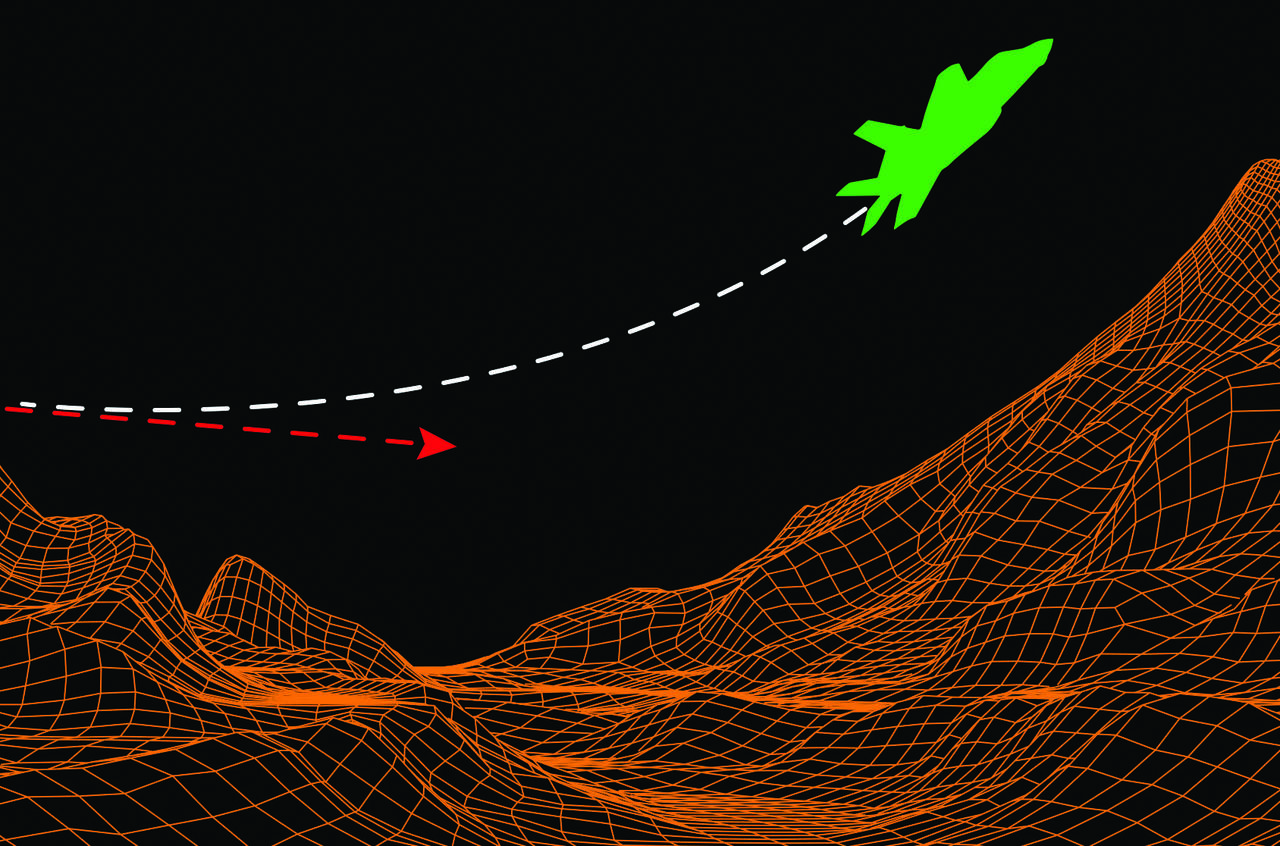

Automatic Ground-Collision Avoidance. Image courtesy of Lockheed Martin

A test pilot who worked on the F-16 and F-35’s automatic ground-collision avoidance system (AGCAS) predicts the system’s inclusion on commercial jets before too long, but major original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) Boeing and Airbus said there aren’t any plans for such technology in the near future.

AGCAS uses GPS to monitor distance from the ground, taking current terrain into account. If the vehicle goes past the point where a pilot would be able to react, it seizes control, steers the plane out of harm’s way, then returns control to the pilot. The thought is that if the pilot were conscious and had his or her bearings, they would have reacted by that point. Flynn said that extensive testing showed 1.5 seconds to be the final point by which a cognizant pilot would be able to prevent a crash, so if they hadn’t reacted by that time, the system could safely assume it is an emergency situation and take control, giving the pilot time to recover from a blackout or reorient themselves.

To date, the system has saved the lives of eight F-16 pilots and seven F-16s. It will soon be added to the F-35, five years ahead of the original schedule.

“This technology is so interesting that it’s going to end up in corporate jets,” said Billie Flynn, a Lockheed Martin experimental test pilot who helped develop the system along with Air Force Research Lab engineers at what is now the NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center. “It’s going to end up in private airplanes that people fly, and it’s going to end up in commercial airplanes that you and I load onto every single week. … At some point, you’re never again going to hear about airplanes crashing into the ground, into swamps, into mountains.”

It’s hard to predict exactly when that will happen because it’s partially a business decision and industry tends to move slowly, Flynn said, adding the military is always the early adopter of new technology and takes care of risk reduction, a process which is mostly complete.

“I think we’ve solved the problem,” Flynn said. “I think we worked really hard in the F-16, we’ve flown it operationally now four — I don’t know — three or four years. I think we know a lot about how it works, and that’s why we have so much confidence now that when we put it in the F-35 it’s very likely to work right off the bat.”

He also said scaling up to even a large airliner doesn’t change much.

“It will not be a technically challenging effort,” he said. “A bunch of technologies came together and that’s why it became so easy for us to develop our system in two years (after 25 years of flight testing) on the F-16. Do I think it’s hard to develop a system for an airplane like a 737 or an Airbus airplane or any flying vehicle? The answer is no.”

A source at Airbus debated that characterization, saying there are limitations that add complexity. They said that the European manufacturer has looked into such a system but is not actively pursuing it and that it did not find a market for a similar system aimed at reducing potential collisions during taxiing.

Similarly, a Boeing spokesperson said that the American plane-maker has seen no customer interest in such a capability and that it “has not identified any economic or safety benefit for this function.”

He also said that the company has concern that retraining pilots from the current protocol of manual terrain and obstacle avoidance if the terrain awareness warning system were coupled to the autopilot would require a significant time and money investment beyond the cost to certify and retrofit aircraft for the functionality “for no apparent benefit.”

Lastly, Boeing’s “flight crew philosophy has been for the pilot to remain in full control” during pull-up and traffic-alert collision-avoidance maneuvers.

For his part, Flynn made it clear that the AGCAS team made it a priority to keep the system as unobtrusive as possible, kicking in as a last resort, only after a pilot would no longer be able to react, rather than wresting any normal avoidance tasks away from them.

“It won’t take over early from the pilot — whatever task we’re doing we will be allowed to do — but if we were way too close to (hitting) the ground, it would take control and save us.”

Commercial pressure is what he said could get OEMs to start including the system on their planes, though the big two said they haven’t felt any such pressure and don’t see it happening any time soon.

Flynn thinks it might be sooner than they make it sound, though.

“YouTube the F-16 video that shows the system saving a guy’s life,” he said. “It has become so compelling that I bet you it is not an exceptionally long time until commercial and corporate aircraft builders find a way to put this into their airplanes.”