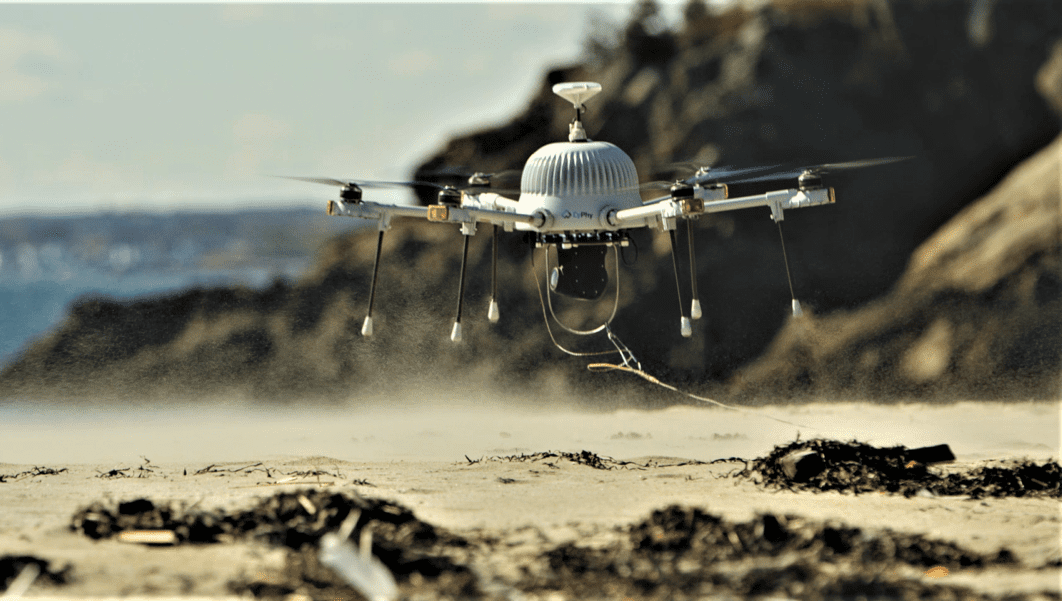

CyPhy Works’ PARC tethered drone. Photo courtesy of CyPhy

The U.S. Army and Navy Special Ops use drones from CyPhy Works to get around one of the big hindrances with most unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), a lack of persistence engendered by the need to frequently recharge the batteries.

Founded in 2008, Massachusetts-based CyPhy supplies tethered drones. What the drones lack in range, they make up for in endurance, with flight times having exceeded 220 hours, or nine days, according to VP of Business Development and Strategy Matt Stevens.

“With a tether, as long as you have power going up, you have flight,” Stevens said at Modern Day Marine last month. “Battery life limits other drones.”

The company’s persistent aerial reconnaissance and communications (PARC) system is made to be as intuitive and expeditionary as possible. The drone weighs about 13 lb on its own with a payload capacity of an additional six and can fly up to 400 ft, at which point it reaches the end of its rope. Both the payload and the UAS itself are modular for easy transport and flexibility, and it can be assembled in minutes. “If something happens, you can replace a leg, replace a prop, replace a strut” while out in the field, Stevens said.

The PARC’s most cumbersome piece of equipment is the robotic spooler and the reserve of high-voltage, copper-twisted kevlar tether that the spooler lets out and retracts to allow the unit to fly. It can be placed on the ground, but the most flexible way to use it is mounting it in the back of a vehicle. That way, it’s ready to go on arrival, and the team just needs to take a few minutes to set the UAS up and can get the mission underway. Then, if they finish with the current area or the operation shifts, the team can descend, move the vehicle serving as base and head back up, vastly increasing the PARC system’s range.

“Stop to launch is a minute and a half,” Stevens said. “Take it down, a minute and a half. Just drive to the next spot.”

Like Stevens, many employees at the 40-odd-person company are ex-military, which made the U.S. Defense Department a natural first customer. They knew how much of an issue constantly retraining soldiers is, so they made sure the PARC could be effectively operated by “any soldier, any sailor, any marine” with two days’ training. It can be left to fly autonomously while the operator controls the camera, and if there is a power loss, a backup battery would engage while the drone lands itself.

Operation is done from a proprietary, laptop-based ground control station. Unlike many companies, CyPhy avoids the cloud and keeps the network closed-loop to ensure security. That network can be meshed with those of other PARC units; however, letting a handful of units quickly set up a series of connected networks that combine to cover a wide area.

“This is a huge force multiplier because it is getting you above the treetops letting you see the terrain,” Stevens said.

The PARC drone is designed to be flown in inclement weather “if a small unit makes that risk assessment,” and its payload agnosticism gives it great flexibility. It can handle electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR), long-distance scouting and recording, or it can be equipped with a 4G LTE payload and sent up to function as a temporary cell tower.

It’s for this reason that CyPhy sees applications in border patrol, security and asset inspection. While most of the company’s business has been with the Defense Department so far, CyPhy pitches its product to all of those industries — as a cheaper alternative to helicopters, a low-training inspection tool and rugged and equippable with hazardous material sensors for use in mines or the energy sector. The company even promotes its nominal downside, its “leash,” as a positive that prevents flyaways in bad weather.