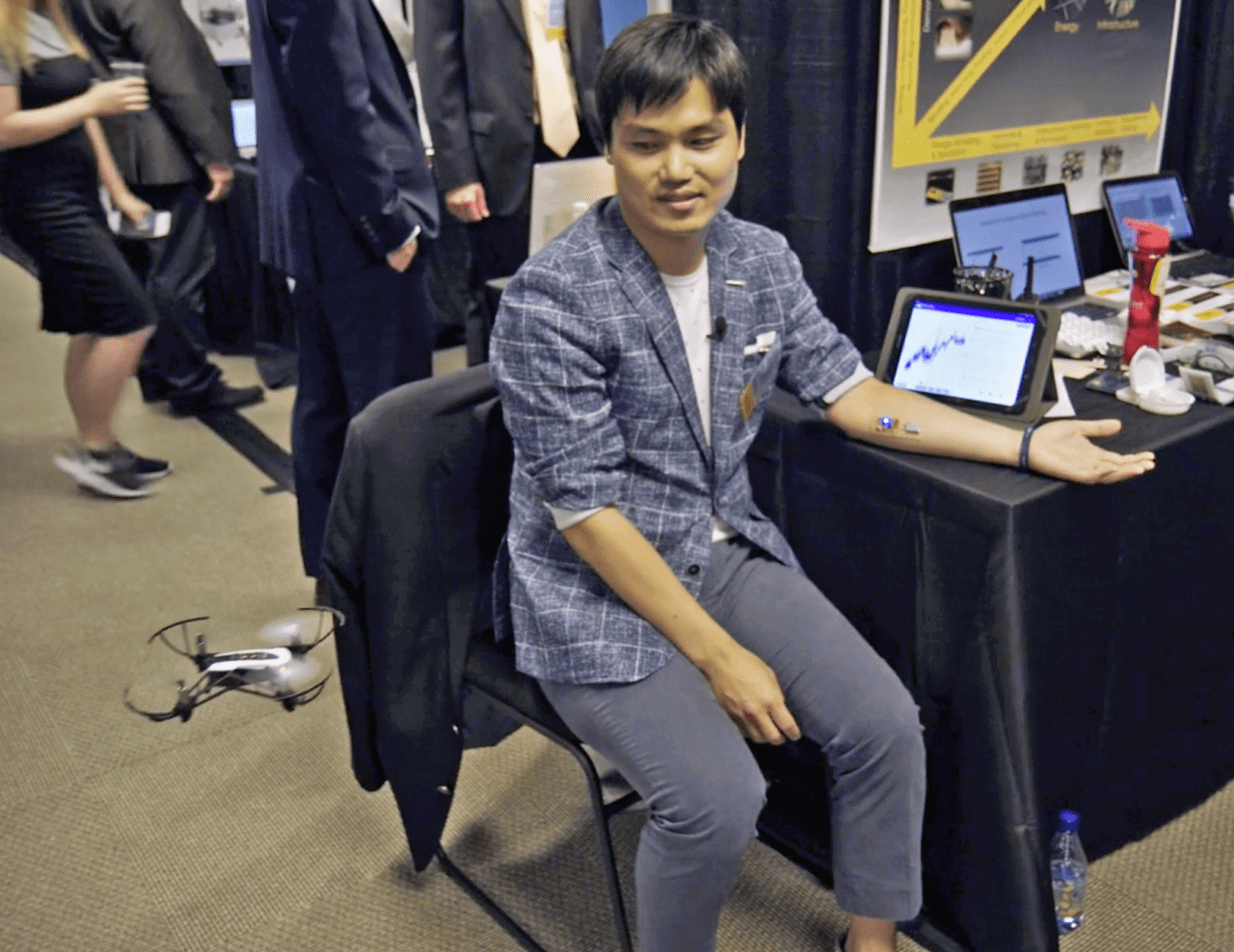

A demonstrator controlling a small UAS with a NextFlex patch on his forearm. (AVI screenshot/NextFlex video)

Controlling drones is an arms race of user-friendly input devices.

In the interest of meeting operators where they are comfortable, companies have gone from bulky proprietary ground stations to commercial laptops to tablets to video game controllers.

NextFlex is letting you use your body. Just slap on a patch, and you’re ready to go.

The California-based public-private partnership works with flexible hybrid electronics (FHE), which are essentially “equivalent to a printed circuit board of electronics,” but bendable, according to Executive Director Malcolm Thompson. There are myriad uses for the tiny, flexible, rugged communication chips, including sticking one to somewhere like the back of an operator’s hand. From there it can detect electric currents so the operator can control a drone through movement, without the need for additional equipment.

“It’s really very much a manual operation,” Thompson said. “The individual with the circuit is actually controlling it continuously in terms of speed and direction.”

Of course, a paradigm shift like that does require some training, and the chips must be calibrated for individual operators. Thompson said the control is very precise, which demands that the settings be as well.

The chips are flexible Arduino boards that are one-third the weight of traditional rigid ones, Thompson said. Digital designs are sent to a printer, which prints silver conductors, insulators and even components such as resistors and capacitors onto a polymer substrate. When a silicon chip is incorporated, it’s thinned down to 50 microns or less to cut down on weight and size.

Battery life varies based on usage, but is on the order of days or weeks, Thompson said. The biggest drain is the communications chip — whatever is sending the signals the chip picks up over Wi-Fi or another type of network to control the drone. The main method of recharging is the cannibalization of other available signals, according to Thompson

“It captures various communications or noise out there and converts that to charge the battery itself,” he said.

The technology, which Thompson calls “a new generation of electronics” is interesting to many. NextFlex only has 31 employees, but there are around 100 members of its partnership, including companies such as Boeing, Lockheed Martin and GE; government organizations such as NASA and the Army and Air Force Research Laboratories; and schools such as the University of California, Berkeley and Georgia Tech, where much of the drone research has occurred.

Since its founding in September 2015, NextFlex has received $75 million in contracts, including a recent $20 million contract from the U.S. Defense Department (DOD), for the FHE technology.

Its partnerships with these companies pay off in two main ways: relationships and supply chains. Thompson said NextFlex often finds itself putting a large company in contact with smaller startups that are part of the group and specialize in something relevant.

“Boeing will say, ‘We’d never be working with these companies if they weren’t part of your network.’ We’re a bit of a marriage broker,” Thompson said.

NextFlex also benefits from the manufacturing footprints of the big companies. It has in-house facilities where it can make its own products, but only on a small scale. When one of the bigger companies is interested, it can take the design and scale up what NextFlex develops, creating a convenient and mutually beneficial supply chain, he said.

The technology has attracted the attention of the DODt. The same patches that allow operators to command small UAS with their hands could be made compatible with an MQ-25 or a Black Hawk with an automated flight system installed, Thompson said.

DOD also is interested in using the technology as a wearable patch to link troops to vehicles, computers and the overall system for tracking and identification of troops. If something happens to a soldier, the tracker would alert the system and opposing forces would be locked out of their equipment.

NextFlex and Boeing are researching printed FHE sensors applied along the side of an aircraft to act as an antenna array. They can be as large — and, therefore, as powerful — as a manufacturer wants without requiring an obtrusive additional antenna attached to the aircraft’s fuselage.

Most of the projects NextFlex takes on involve a company and a university working in concert. Companies are often “trying a whole range of different types of sophisticated applications” involving their products, he said. Potential applications of FHE could be endless and unforeseen, he added.

“There’s a lot of flexibility,” he said. “There’s really no constraints in how we can do this.”