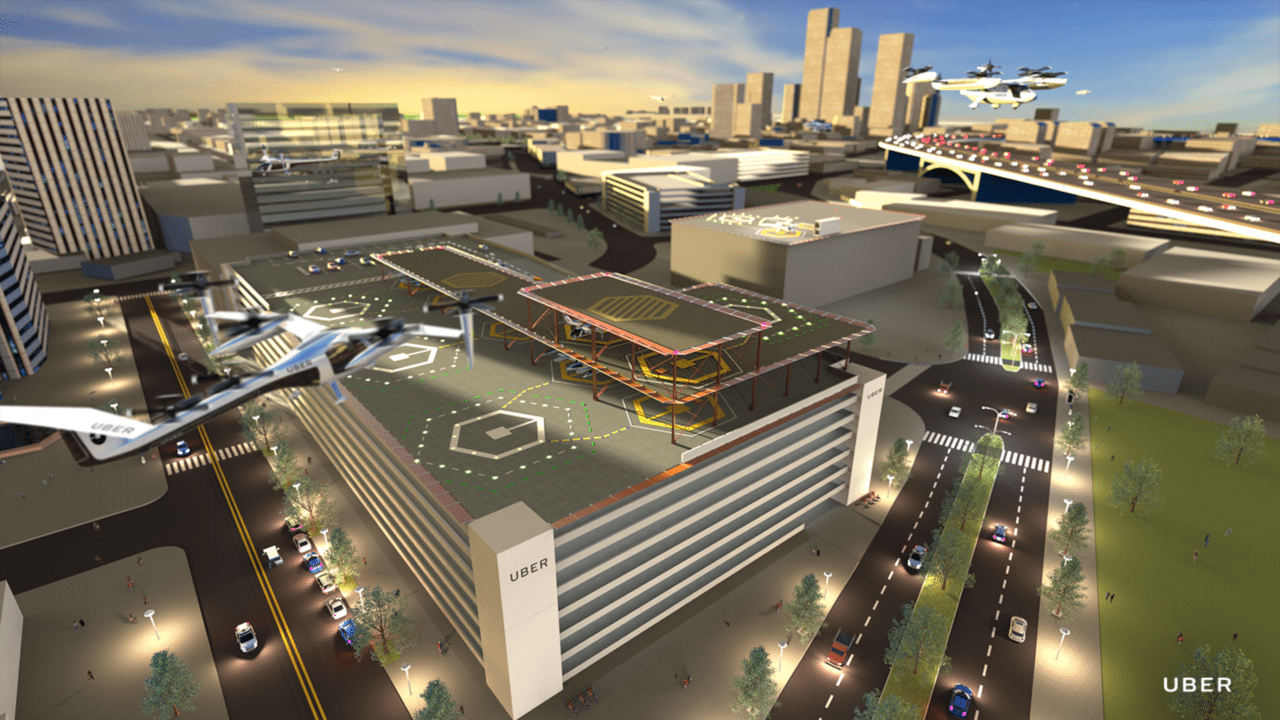

A rendering of an Uber vertiport. (Uber)

Uber’s key to successfully scaling air taxis up to mass transportation level lies in the vehicles having fundamental advantages over helicopters, according to Engineering Director of Aviation Mark Moore.

Speaking Wednesday at a Georgia Tech event on urban air mobility and its future for the state, Moore said that they have the edge over helicopters in urban mobility when it comes to safety, cost, noise and efficiency thanks to distributed propulsion and electricity. Those factors will let the rideshare company push its air taxis past the elites-only price-point that helicopter urban transit has always held.

Helicopters generally have a single point of failure, often a main rotor retaining nut, dubbed the “Jesus nut” due to its ubiquitous criticality in linking the cabin to the rotor. With the five experimental air taxi vehicles that Uber’s partner companies are building, all of which are fixed-wing, electric or hybrid-electric vehicles, control and thrust can be distributed across the platform so that a single part failure won’t bring it down, said Moore, who spent three decades working at NASA. That redundancy means greater safety.

It also is one way to save on operating costs. The fact that helicopters feature that single point of failure means they require very frequent, thorough inspections. Fewer inspections and eschewing fuel costs for electric propulsion cut down on the high operating costs for helicopters. Further, Moore said that most helicopters are made in small batches, which prevents them from really benefiting from economies of scale like an automobile would. That will be the same for the first batches of air taxis, he said, but as Uber is able to scale up beyond 50 vehicles per batch into luxury car numbers and beyond, the cost per vehicle will drop.

Noise is one challenge facing aerospace innovation. Communities are hesitant to accept new travel that will disrupt daily life; supersonic flight is contending with the same issue. Air taxis can make less noise than helicopters in the first place by cruising in wingborne rather than edgewise flight, according to Moore, and slowing down the tip speed the right amount allows further noise reduction by about 15 decibels, which is he said is enough to blend into ambient city noise.

Uber also has a two-fold plan to mitigate the effects of the noise pollution it will create when it adds an initial 150 and eventual 1,000-plus takeoffs per hour at each Skyport: First, the company intends to keep all Skyports, even eventual dedicated ones, on the tops of multi-story structures so that the source of the noise is elevated off the ground. Second, Uber aims to place Skyports “always close to a major artery, like a big roadway” that already creates noise, letting the additional air taxi noise blend in, according to Moore.

Increased efficiency is a big benefit and stems from the compounding effect of using fixed wings rather than rotors and using motors rather than turbines, according to Moore. The wings allow at least quadruple the lift-to-drag ratio of rotors, while using the electric motors allows triple the propulsion efficiency. As such, the vehicles can be 12 to 16 times as efficient as helicopters, Moore said.

Uber plans to begin experimenting in its launch cities in 2020, beginning with Dallas and Los Angeles as well as a city outside of the U.S. Initially, Dubai was the pick, but delays have opened the selection process back up; Moore said the company will announce a selection for the final city “in the next few months,” and that the company is looking at cities in Australia, France, Brazil, Japan and India.

The proper service launch in those cities, Uber says, will be in 2023.

Scaling up and making the numbers work is all about the price per passenger mile, Moore said. Helicopter flights cost about $9.00 per mile — too high to be sustainable. Once 2023 comes, demand for the product can start to help the economies of scale, reducing a cost that Moore said will already be far lower than that of helicopters. If the company gets an average load factor (in the airborne equivalent of Uber’s ridesharing Uber Pool service) of 2.7 to 3 passengers in its four-seat (plus one pilot) taxis, Moore said that it can get the price per passenger mile down to $1.84, which is comparable to Uber’s ground service.

Barring any problems, three enabling factors can then take effect. Expanding to more sites and cities will allow scaling that drives prices down. At the same time, next-generation battery technology is hopefully ready to improve vehicle performance and the power-to-weight ratio — something the company and burgeoning industry as a whole is counting on. And, eventually, pilots will be unnecessary, Uber hopes. That has the two-fold effect of removing one of the company’s largest costs (pilot salaries) and adding an additional seat in each air taxi.

Removing the human element might also make things more reliable.

“For us to be able to fly thousands of aircraft, we need to get rid of that uncertainty of pilots,” Moore said.

That should take about five years after the service launches, according to Moore. Uber expects “on the order of 100 million trips” needed with a pilot as a fallback before the FAA is comfortable certifying the autonomous flight safe enough to remove the pilot.

If all that goes as planned, Moore painted a picture of getting the cost per passenger mile down as low as 50 cents. “That’s when it can essentially compete with your private car, and that’s when it’s a really compelling mass transportation solution,” Moore said.

Of course, there are a lot of obstacles before that happens. It relies on battery technology developing. It relies on the FAA’s certification of autonomous flight. It relies on FAA National Airspace Systems regulations changing considerably regarding spacing between aircraft — Uber is counting on well over 1,000 takeoffs per hour at busy Skyports, which would currently be illegal. And it relies on the ready adoption of the new transportation method by a public which soured on helicopter-borne urban mobility decades ago. With all of those challenges, the industry — and Uber’s ambitious timeline — faces many skeptics.

There’s good reason to try, though. The average driving speed in Los Angeles, one of Uber’s launch cities, has slowed from over 40 mph in the 1970s to the mid-20s today, according to Moore. And Google-collected data shows the slow-down is even worse in cities such as New York, San Fransisco and Washington, D.C.

“What did cities do…to maintain productivity as they tried to grow and thrive?” Moore asked. “They grew up, literally; they utilized the third dimension. That’s what we’re trying to do.”