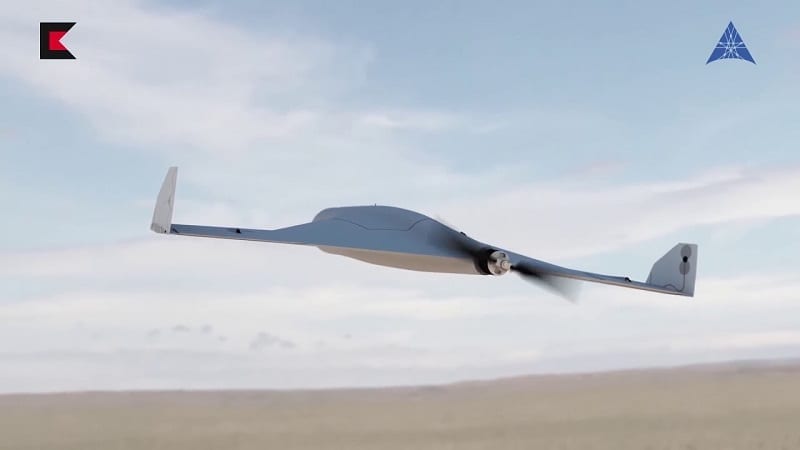

The Russian KUB-BLA drone

Ed note: Originally published on our sister site, Rotor & Wing International, which covers rotary wing aircraft.

Russia’s ZALA Aero Group, the unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) division of Kalashnikov, unveiled a “kamikaze” drone — the KUB-BLA — at the International Defense Exhibition and Conference (IDEX) in Abu Dhabi on Feb. 17.

The small UAS is designed to have a maximum speed of about 80 miles per hour, an endurance of 30 minutes, and an explosive payload of 7 pounds against “remote ground targets.”

Loitering munitions can have a dwell time up to six hours and are equipped with sensors to allow the drones to detect and attack targets independently. Early 1980s-era examples include Israel Aircraft Industries’ Harpy suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) drone and the U.S. Air Force AGM-136 “Tacit Rainbow” SEAD system by Northrop Grumman — a $4 billion development program canceled in 1991.

Sergei Chemezov, the CEO of Rostec, the Russian state-owned defense and high technology conglomerate, said at the IDEX show that the KUB-BLA “is an extremely precise and very effective weapon, incredibly hard to fight by traditional air defense systems.”

“The explosive can be delivered to target regardless of how well hidden it is,” he said. “It operates regardless of hidden terrains, at both high and low altitude.”

ZALA Aero said that the advantages of KUB-BLA include “high accuracy, hidden launch, noiselessness, and easy to use.”

The unveiling of the KUB-BLA comes as countries consider the implications of artificial intelligence and lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS).

In the United States, the Aerospace Industries Association said that the recent revisions to the Conventional Arms Transfer Treaty will provide flexibility to allow domestic aerospace companies to export innovative UAS to other countries, and the association is calling for a further review to prevent such systems from falling into the wrong hands.

“The definitions of things like cruise missiles and ballistic missiles were set long before some of this technology was imagined,” Eric Fanning, the president of AIA, told reporters last week. “And various UAS – whether it’s for urban air mobility or long-range, large cargo vessels – are pushing up against those definitions. So, what we’re calling for is the review of them to see how we can delineate between, for example, what’s a cruise missile and what’s a UAS cargo craft. We’re calling, specifically, for review of weight, speed, and range, to see if we can’t use those as indicators, to try and separate what those are. Obviously, we care about making sure that we are careful about proliferation and doing what we can to protect proliferation, anti-proliferation efforts. We want to make sure that we’re not needlessly stifling innovation growth and market opportunities.”

In the past, countries such as the UAE, Jordan and Saudi Arabia were denied in their requests to purchase U.S. drones, and China stepped in to become a supplier. Under the Missile Technology Control Regime, the Trump administration has advocated facilitating the export of any UAS, such as the General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper, that flies under 650 kilometers per hour.

The administration’s Conventional Arms Transfer Policy, announced last April, says that among the considerations involved in the executive branch making an arms transfer decision will be “the recipient’s ability to field, support, and employ the requested system effectively and appropriately in accordance with its intended end use” and “the risk that the transfer could undermine the integrity of international nonproliferation agreements and arrangements that prevent proliferators, programs, and entities of concern from acquiring missile technologies or other technologies that could substantially advance their ability to deliver weapons of mass destruction, or otherwise lead to a transfer to potential adversaries of a capability that could threaten the superiority of the United States military or our allies and partners.”

A United Nations’ working group on lethal autonomous weapons is to meet on March 25-29 to consider the potential challenges posed by emerging LAWS technologies to international humanitarian law. The working group of governmental experts functions under the High Contracting Parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons — a 1983 treaty signed by 125 countries that seeks to prohibit or restrict the use of certain conventional weapons, such as landmines, which are considered excessively injurious or whose effects are indiscriminate.

“LAWS present unique ethical challenges around the question of humans giving up responsibility for killing by fully transferring decisions over life and death to machines,” Ulrike Esther Franke, a a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), wrote in an ECFR column last November. “While for centuries now, previous technological advances have gradually increased the distance between humans and the act of killing, LAWS for the first time allow a complete removal of the human from decision-making.”

At an International Committee of the Red Cross meeting in Switzerland in March 2016 to discuss the implications of autonomous weapons systems, Vadim Kozyulin, the project director of emerging technologies and global security at the Moscow-based PIR Center for Policy Studies, said that “Russia has no armed drones for now, although they are being developed, which shows that Russian drone designers are about 15 years behind their American counterparts.”