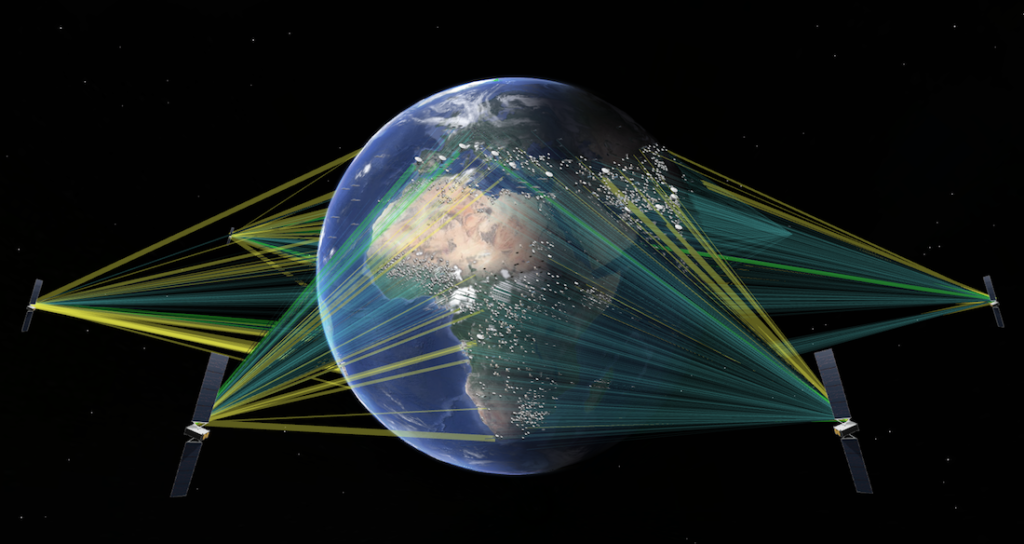

A computer rendering of the SES 03b mPOWER satellite constellation. Photo: SES

SAN DIEGO — SES wants to use its next generation satellite constellation, O3b mPOWER, to provide increased capacity to airlines for in-flight connectivity, while also considering how to establish a new end-to-end business model that partners aviation and ground-based internet service providers.

The satellite service provider is in the midst of launching seven satellites for 03b mPOWER by 2021 in a medium earth orbit (MEO) constellation. Aditya Chatterjee, senior vice president of the aero market at SES, said the new constellation will have 30,000 fully-shapeable and steerable beams that can be maneuvered in real time to adjust to changing bandwidth needs.

“We’re launching seven satellites that will be dedicated to mobility services, and the aero market has become one of our biggest users,” Chatterjee said at the Global Connected Aircraft Summit hosted by Avionics International. “Recently, we have provided satellite capacity to the biggest aviation service providers including Panasonic, Gogo, Global Eagle and Thales. Now we’re providing them even more because of growing demand for connectivity from airlines.”

O3b mPOWER will cover 80 percent of the earth’s surface and all of the busiest airline routes in the world with satellites capable of digital beam forming. Boeing is the first partner signed up to employ the new constellation, providing phased array technology that will deliver more than 5,000 beams per satellite.

According to Chatterjee, rather than focusing on a Ku or Ka-band, SES is focused on ensuring its aviation service providers have enough capacity to support the current and future internet applications that airlines are seeking to enable such as streaming of real time engine data. He said that the type of capacity airlines are seeking today have significantly increased compared to when SES first started providing commercial aviation connectivity services.

Aditya Chatterjee is the VP of aero for SES. Photo: SES

“Five years ago when we first started in this market, an aircraft was using one megabit. Now, it’s almost become routine for airlines to demand up to 20 megabits to the entire aircraft,” Chatterjee said.

SES also wants to be able to support more advanced internet-fueled applications for passengers as it develops its next generation HTS constellation. One example of the generational leap for in-flight connectivity that has already occurred on newer in-service airplanes is the use of audio and video streaming applications, which Gogo’s 2Ku service can support whereas its previous air to ground network could not.

Chatterjee said some of the next generation in-flight applications include more use of virtual and augmented reality as well as interactive gaming applications for passengers. The majority of those applications will use MEO or LEO satellites, as the GEO satellites are simply too high in altitude to support that type of bandwidth consistently.

Beyond capacity and next generation applications, a major focus for SES is to establish new partnerships with ground-based internet service providers that can help facilitate end-to-end connectivity for the entire journey of an airline passenger. Rather than using a different service provider at home, in the airport and on the airplane, SES wants to establish a new business model where the passenger is using the same satellite network across all three locations without having to constantly switch.

“Connectivity on the aircraft is becoming a mandatory requirement, and it’s not paying for itself,” Chatterjee said. “Today, we sell our satellite capacity to the aviation service provider, and they have to then install equipment and sell the service to the airlines. The airline then says, if my passengers use your service, I will pay you, but only if I get paid. That leaves only one person taking the risk, the aviation service providers, and they can’t keep doing it this way.”

Instead, in the future, SES wants to use new application programmable interfaces and partnerships with cellular and home-based internet service providers such as Verizon or Deutsche Telekom that would give passengers the ability to keep their device connected to one network on the ground and in the air. He describes this as the industry shifting to a risk-sharing model, rather than placing the majority of the risk on the aviation service providers.

Chatterjee also believes that if more airlines can find real value in reducing aircraft time on the ground through predictive maintenance and access in real-time to aircraft component data, they can consider their in-flight connectivity investment as a potential savings rather than a risk.

“There are going to have to be changes in the business model for providing in-flight connectivity,” Chatterjee said. “We’re increasingly looking at how we can partner with the terrestrial service providers to create more of an end-to-end network where there is less risk placed on one entity or another.”