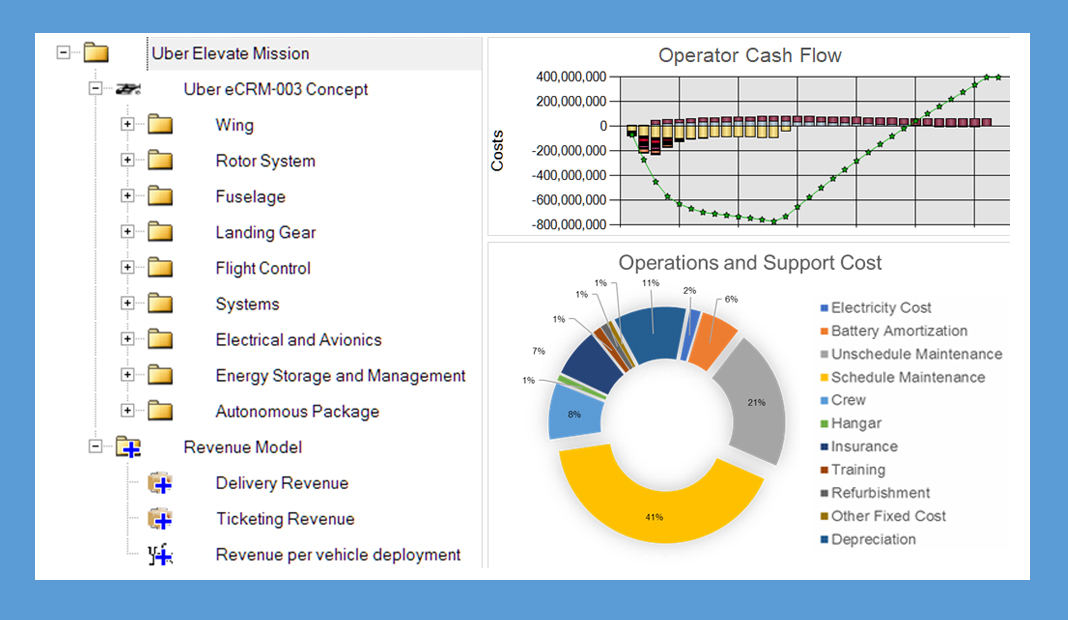

PRICE Systems’ TruePlanning cost analytics software in use evaluating Uber’s eCRM-003 concept vehicle. (PRICE)

With the goal of pioneering a potential $500 billion new industry and an aggressive timetable, Uber wants to know how it can make money. That’s where PRICE Systems’ cost analytics service comes in.

For Uber and manufacturing partners Bell, Karem and Jaunt PRICE takes into account every planned specification, existing comparable, known certification hurdle and expected maintenance timeline to estimate life cycle operating cost for electric vertical-takeoff-and-landing vehicles. Then, each time one of those manufacturers suggests a tweak to a part, PRICE adjusts the model and starts over. Uber’s remaining two manufacturing partners, Embraer-X and Pipistrel, are not clients of PRICE.

Uber is targeting $700 per flight hour, including the amortization of development costs, construction, operation and maintenance and pilot salaries. Can it get there?

“It’s certainly challenging, 2023 is certainly challenging,” said PRICE CEO Anthony DeMarco, who led the company’s 1998 breakaway from Lockheed Martin. “But, if I look at what Jaunt is doing and all the other partners — they’re pushing hard… Every concept has some technical challenges. Talking with teams and suppliers, the suppliers seem to be up for the challenges. There’s definitely optimism throughout the supply chain.”

The biggest roadblock, DeMarco said, is certification, because regulators such as the FAA “haven’t really nailed down exactly what the certification [standards] are going to be.”

Another area of significant uncertainty is infrastructure. The PRICE TruePlanning cost analytics software doesn’t include the price of Skyports or building any infrastructure, but it does need to make assumptions about their prevalence and the availability of line-replaceable units in different locations, whether maintenance can be done at a Skyport or the vehicle will need to be transported for work.

“When an estimate has to be made, that’s usually when the rubber meets the road,” DeMarco said. “All the engineers are talking about these different concepts, then the cost estimator says ‘Okay guys lets put these ground rules down.’ They’ll change, but you start assuming this many Skyports, this many days of supply, and they’ll store this many supplies.”

DeMarco said that PRICE relies on Uber’s whitepaper, “Fast-Forwarding to a Future of On-Demand Air Transportation,” for many of the assumptions, and learns more from existing rotorcraft markets.

“A lot can be learned from commercial rotorcraft, military rotorcraft, but there’s uncertainty,” he said. “Uber has started with that route from Manhattan to JFK [with Uber Copter] to get some of these things going so that we learn so that we reduce some of the uncertainty. As we move into this, we can get a better idea of what the infrastructure is going to be.”

In the meantime, though, that uncertainty means gray areas in the estimates.

Want more eVTOL and air taxi news? Sign up for our brand new e-letter, “The Skyport,” where every other week you’ll find the most important analysis and insider scoops from the urban air mobility world.

PRICE also models risk in addition to cost, so with any given model, users can see the chance of that projection being accurate based on the confidence of its underlying assumptions as well as an outcome range.

“How sure are you on certification, how sure are you on the reliability of the landing gear, how sure are you on the weight of the battery?” DeMarco said. Based on factors like that, the system will spit out an expected range. So, while $700 is the target and there’s a chance the result falls under that if things break right, “you can also be 80 percent confident that the cost will be $900 or less based on that design.”

There are a lot of requirements that each of these vehicles has to meet — safety, weight, endurance, noise, cost. Making an improvement in one might detract from another.

A manufacturer “might say ‘Hey, if we can do this, we can get an extra five miles out of a charge,’ DeMarco said. “But what does that mean? More weight? You’re constantly balancing these criteria against each other. It might increase mean time for failure, might hurt safety, might increase cost per mile because we have to bring it in for overhaul more often.”

Since the Uber partners are all trying to fulfill the same mission, DeMarco said the model looks the same for them all at the top level, looking at major subsystems, but it starts to differ more as things get nitty-gritty. Particularly given that different competitors are looking at different alternate uses for their vehicles, from cargo to search-and-rescue to medevac, the lower-level modeling starts to get much more tailored.

“What it looks like now is constantly plugging it into the model to see how it’s going to affect these things,” DeMarco said. “What it looks like now is design tradeoffs.”

UPDATE, 7/25: This article originally listed Boeing subsidiary Aurora as a client of PRICE’s. DeMarco misspoke, and the article has been updated to accurately reflect that Aurora is not a current client.