As a number of companies including Boeing, Bell Flight, Volocopter and Sabrewing (among others) are developing electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft for various cargo delivery and passenger carrying missions, two companies, Metro Hop and FLUTR, are taking disruptive approaches toward the future vision of urban air mobility (UAM) that has the aviation industry in a frenzy right now.

Following the recent Revolution.Aero event in San Francisco, California, Avionics International caught up with leadership from both companies to gain a deeper understanding of the aircraft they’re developing.

Metro Hop: Electric STOL Cargo Delivery

Forestville, California-based Metro Hop proposes using short takeoff and landing (STOL) electric aircraft to move goods from fulfillment warehouses to, for example, hospital campuses located within city centers.

As a conventional airplane rather than rotary/fixed-wing mix, Metro Hop’s design would be able to reach speeds up to 220 knots, using specialized landing gear to take off and land with just 200 feet of runway and offering 1,000 pounds of useful payload with a range of 125 miles.

“The big hospitals are in city centers or densely populated areas,” Mombrinie told Avionics. “They don’t have a lot of room for storage, and they tend to order things express delivery … so that market is not really sensitive to price, and there’s a huge volume there.”

Metro Hop’s airplanes would offer an improved price point and speed of delivery over trucks or company vans currently making these delivery trips, according to Mombrinie, allowing for considerable profit margins. The company also plans to develop a passenger-carrying version of its STOL aircraft for air taxi missions.

However, Metro Hop’s vision includes infrastructure needs that are specific to its airplanes and not interoperable with other designs. In addition to the 200 feet needed for its aircraft to take off and land, Metro Hop intends to employ heavy use of robotics to swap both its cargo bins and batteries quickly. This could in theory enable quick turnaround speeds while eliminating costs and potential for error associated with maintenance technicians, but these systems would likely incur substantial development and manufacturing costs up-front, and wouldn’t function with non-Metro Hop aircraft.

“Everything is geared toward [turnaround] speed, so yeah, this leads to very high initial costs,” said Mombrinie. “The airplanes are robots loaded with sensors, so they’re very expensive … the infrastructure at the skyport, we’ve got these moving robots that swap out batteries as the planes are moving along.”

This investment would enable high numbers of Metro Hop planes to arrive and depart from each landing structure, with promotional footage envisioning a conveyer belt-like system that allows for six planes in and out per minute, with three-minute turnaround times per airplane, according to Mombrinie.

“The skyport becomes a very dedicated part of the machine. You can think of the whole robotic system of all the planes altogether as one organism of sorts,” he said.

Metro Hop’s vision of quick-turn, at-scale cargo and passenger planes will require a massive amount of investment that is predicated on the success of a single system that isn’t interoperable with other aircraft designs, but the company believes the clockwork-like operations will be worth the initial cost.

Mombrinie estimates it will cost $25 million to develop the cargo-carrying airplane, allotting three years to develop the final product and potentially five more to certify it. He believes Metro Hop’s designs will have an easier path to certification than many others in this space, as it involves less deviation from existing planes.

FLUTR Motors: True Door-to-Door Flight?

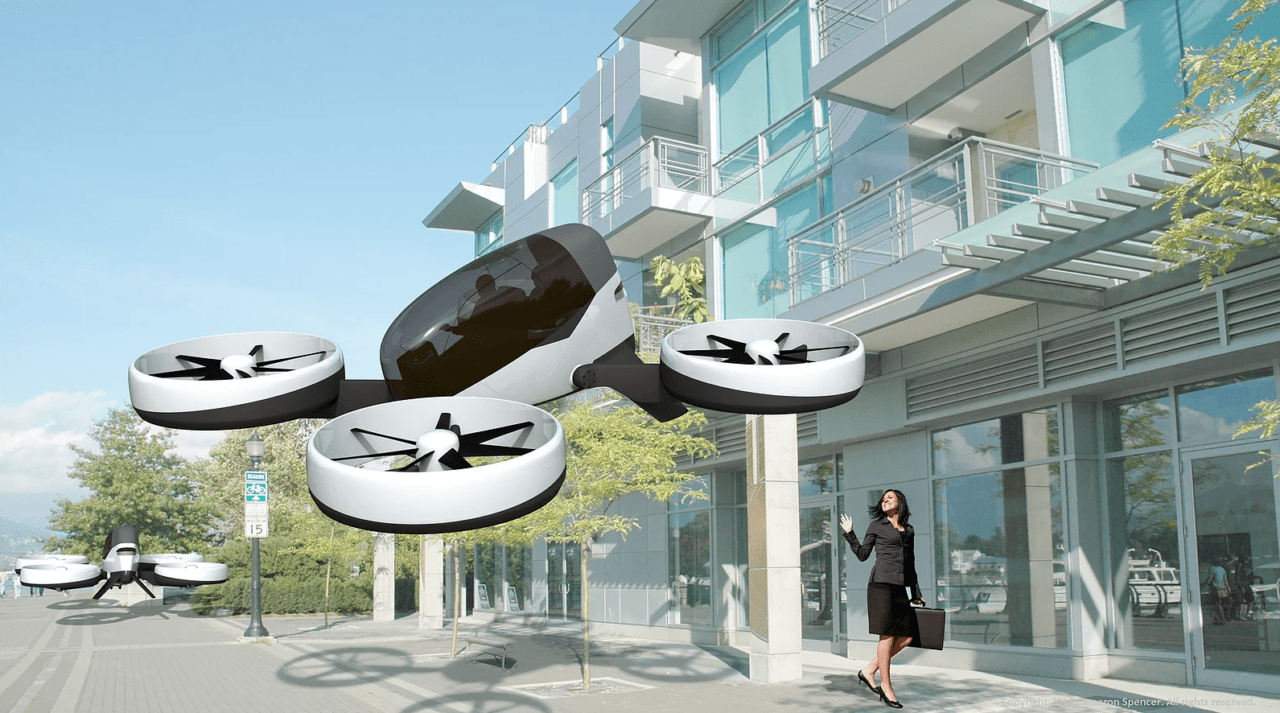

Photo: FLUTR Motors

As the UAM vision crystallizes around a network of vertiports that, much like airports, are likely not passengers’ final destinations, a few designers are hoping to create true door-to-door flight through a personal air mobility future that isn’t limited by landing infrastructure.

Munich, Germany-based FLUTR Motors is building a bio-diesel-powered personal aircraft with four tilting ducted rotors, capable of flying 125 miles at a top speed of 155 mph. It isn’t really a flying car since its slow-speed electric wheels aren’t designed for more than moving the vehicle around a driveway or garage, but who needs wheels when you can fly above traffic?

Cameron Spencer, CEO of FLUTR Motors, doesn’t believe the urban air mobility vision is viable in dense cities due to regulatory constraints, long approval times and concerns around noise pollution, which he believes will restrict the placement of heliports in city centers.

“Everyone has this vision that you can go straight to the center of Manhattan,” Spencer told Avionics. “Even though there’s helipads on buildings, it’s not going to happen because of the noise … If you want to go around the city, or stay on one side of the city, or go away from the city, then [flight] is perfect. But going directly into the city, it’s a nonstarter.”

As a result, Spencer’s vision for FLUTR might be defined as suburban air mobility. The vehicle requires a circular area 26 feet in diameter to land, such as a parking lot, yard or low-traffic street.

“You can’t get ultra downtown with these things because of the noise,” Spencer said. “It’s more about slightly outside, maybe five to ten kilometers outside the city center, where you’ve got industrial areas, highways, residential areas — that’s the sort of area you’re looking at.”

In less populated areas, this would be true point-to-point air mobility — and FLUTR’s vision for the ecosystem surrounding the car is designed to enable just about anyone to fly, as long as they can get past the vehicle’s estimated price point of $199,999, though the company also plans to offer $4 by-the-minute usage rates.

Spencer wants customers to be issued a “FLUTR license” and ready to fly after just a weekend-long training course. His vision is for the vehicles to be mostly automated; passengers would enter their destination, leave the ground and then let the autopilot take them the rest of the way. Passengers would be strictly limited by this license in terms of what they can control, able to change their flight path, hover up to 100 feet and pick a landing spot.

In-progress trips would be overseen by a group of FLUTR-employed remote pilots, or managers, according to Spencer, available to intervene if a customer encounters difficult weather conditions or needs other assistance. Access to this resource would cost a monthly fee.

FLUTR’s demonstrator on display at the 2018 Paris Motor Show. (FLUTR Motors)

The FLUTR team is working on a full-scale demonstrator aircraft, which has hovered off the ground but has yet to achieve transition flight — the team’s next milestone. Spencer is currently looking to close a $10 million Series A and says if FLUTR were funded to the end of the development phase, the team could produce a finished vehicle within 18 to 24 months.

“We’re the only people focusing on what’s called ‘true door-to-door,’ which is one of the hardest aviation things to solve,” Spencer said. “It’s up there with supersonic and hypersonic in my view. So we’re really proud [to be working on it], we think we’re sort of leaders in that area.”

Spencer believes FLUTR’s vision is possible within existing regulations and methods of air traffic control — as long as one flies in uncontrolled airspace, adding another limitation. The company’s website says FLUTR is working with relevant authorities to create its training and licensing program, and seems to gloss over some important and complicated elements of the ecosystem and business model.

For instance, one question in FLUTR’s FAQ asks, Isn’t aircraft ownership complicated? With maintenance, annual inspections, insurance etc?

The answer simply reads, Yes. We will handle this headache for you.

But Spencer is confident FLUTR will catch on quickly once it debuts.

“I think it’d be just like mobile phones and email,” he said. “The first person will get it, then — bang. Everyone will want one and we won’t be able to make them fast enough.”

Advocates for urban air mobility usually point to a clear value proposition for consumers: saving time in traffic-congested cities, traveling either within them or commuting to and from the surrounding areas.

With these exact challenges potentially off-limits for FLUTR, the vehicle’s value seems a bit more difficult to pitch. Assuming the remote-pilot system built around average-Joe pilots can pass regulatory muster and meet the safety standard expected of things that fly.