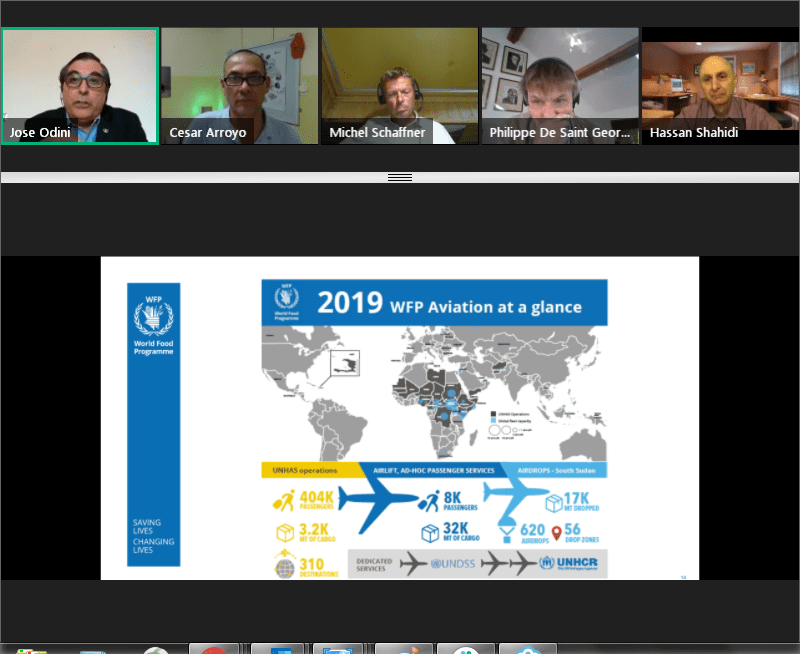

Jose Odini, the chief of the World Food Program’s aviation safety unit, discusses the program’s operations during an Apr. 21 webinar.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the possible utility of drones in beyond visual line of sight operations for the remote delivery of medical and other supply payloads up to 50 kilograms.

“We are following this very closely,” Michel Schaffner, air operations lead for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), said during an Apr. 21 Flight Safety Foundation webinar, “Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic: Humanitarian Efforts.”

“We have drone project initiatives that we have implemented,” Schaffner said, adding that currently there are “limited possibilities due to regulations.”

“Most of the countries are not ready,” he said. “They have not implemented or are not able technically to implement drone traffic into the air traffic. As well, there are some issues of perception because we are working in mostly conflict areas where drones are more seen as a threat, rather than bringing aid. But we hope it will be very useful in the near future, and we’re working hard on that to introduce drone operations, and we’ll see what can be done. Maybe there’s also an opportunity for the future after this pandemic to use drones for types of situations where you cannot physically as a person – you are a threat to the rest of the population – so you go there with cargo and leave without a pilot.”

The ICRC uses 22 manned aircraft and 20,000 personnel to aid people in more than 90 countries – many of them war-torn, such as Yemen, Libya, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, and South Sudan. Among the aircraft are Ilyushin Il-76 and Lockheed Martin C-130 transports and short take-off and landing De Havilland Canada DHC-5 Buffalo and Dash 8 planes. Last year, the ICRC delivered 5,000 tons of cargo.

Hassan Shahidi, president of the Flight Safety Foundation, said that “there has been significant activity internationally to develop regulations that will allow these types of [drone] operations.”

“I think that this crisis actually highlights the usefulness of these types of tools, of drones to deliver medicine and needed material, in these kinds of missions,” he said. Shahidi said that authorities should accelerate the development of standards and regulations for drones “so we can use them more in the field on a routine basis.”

Zipline, a Silicon Valley-based drone delivery service, has been moving medical supplies in Rwanda since 2016. On April 17, working with the World Health Organization, the company delivered 51 COVID-19 tests administered in rural areas of Ghana to its distribution center in Omenako, then to the capital city of Accra for testing and analysis. Zipline had planned for a U.S. launch in the fall, but is working with the Federal Aviation Administration to begin emergency operations in the near future, focusing on the distribution of test kits and personal protective equipment (PPE). Photo: Zipline

A lack of navigation aids in developing nations can bedevil the delivery of humanitarian supplies and may further spur future drone deliveries.

Humanitarian aviation operations by the United Nations World Food Program (WFP) are “mainly carried out in non-controlled airspace lacking navigation aids or taking place in active fight zones, while serving the most vulnerable communities and refugees,” said Jose Odini, the chief of the WFP’s aviation safety unit.

The U.N. aviation program and United Nations Humanitarian Air Service use 90 aircraft – 25 percent of them helicopter – to deliver food and other supplies under the WFP. Such aircraft include the Il-76, the Dash 8, the Airbus A320 and C-295, the Let L-410, the Embraer 135 and 145, and the Bell 412 and Russian Mil Mi-8 helicopters.

“The search for new tools to enhance our cargo delivery capabilities took center stage in 2019,” according to the WFP’s 2019 annual report. “The prospect for the deployment of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) and airships for last-mile delivery of relief cargo is an asset, thanks to the combined effort of WFP supply chain, aviation regulators and industry actors.”