Military and industry leaders agree that funding and available engineering talent are likely to be key challenges for the growing urban air mobility industry. Photo: Agility Prime

As the Air Force seeks to ensure domestic technology leadership in electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft, military and industry leaders agree that funding and available engineering talent are likely to be key challenges.

Where Does the Money Come From?

Through the Defense Innovation Unit, the military has provided some funding to eVTOL aircraft and technology developers, including between $10-20 million to Joby Aviation, according to DIU director Michael Brown, speaking during Agility Prime’s virtual kickoff week.

Agility Prime, the Air Force’s new effort focused on eVTOLs, has awarded Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contracts to Sabrewing Aircraft, Elroy Air and other aircraft developers worth a few million each. But the vast majority of funding for urban air mobility startups has come from the private sector, and the coronavirus pandemic has disrupted fundraising activities worldwide. Analysts have reported 20 to 40 percent year-over-year drops in dealmaking activity.

This has hit the eVTOL sector particularly hard, as the primary source of funding for many well-capitalized startups has been strategic venture funds run by traditional automobile and aerospace companies. Joby’s recent $590 million raise included a $493 million investment from Toyota. Zhejiang Geely, Daimler and JetBlue Technology Ventures have all been active investors in UAM as well.

“Not only does [this crisis] create a challenged operating environment for mobility startups, it’s also creating the same environment for many of their financiers,” Asad Hussain, senior mobility analyst at Pitchbook, told Avionics International. “That affects the funding environment for the startups in the space, and if we hone into urban air mobility, I think there’s a real possibility of technology companies — Tencent, Intel Capital, Nvidia — being in a position to gain a larger foothold.”

Most Silicon Valley-based venture capital firms have avoided the UAM space, according to Kirsten Bartok Touw, founder of AirFinance, for four reasons:

- They prefer software to hardware, eyeing lower development costs and exponential returns

- They avoid capital-intensive industries

- Most funds are built around shorter return-on-investment time horizons than promised by the evolution of UAM

- VCs see great risk in heavily-regulated industries like aerospace

For the U.S. military, there’s a greater concern: the source and motives of capital flowing into defense innovation. A 2018 study by DIUx described early-stage investment in U.S. advanced technology companies as part of China’s “technology transfer strategy,” with Chinese participation in all venture deals reaching 10-16 percent.

Threatened by years of defense-related intellectual property theft by China and other adversarial nations, in 2019 the Pentagon launched its Trusted Capital Marketplace, an effort to vet sources of funding and match them with small- and mid-sized innovative defense companies.

“Trusted Capital is DoD’s forward-leaning approach to confront adversarial foreign investment by offering critical technology companies, including those in the UAS market, funding alternatives to potentially risky foreign investments,” said Jennifer Santos, deputy assistant secretary of defense for industrial policy. “We’ve already lost footing on the small UAS front, and we want to make sure that changes brought about by COVID don’t send us back on the next frontier, eVTOL.”

Trusted Capital and Texas A&M University hosted the first Venture Day in November, focused on small UAS, an area where the United States has largely failed to develop companies able to compete against Chinese industry leader DJI. The group’s focus for the month of May, according to Santos, will be supporting defense supply chains through the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In June, Trusted Capital will partner with the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center to jointly host a venture day for a range of critical technologies including radar, command and control systems, aircraft systems, unmanned aerial systems, data encryption, decryption, robotics, cyber, munitions, and machine learning,” Santos said, adding that her team hopes to expand the program to include sources of capital from U.S. allies.

Where Do the Engineers Come From?

The purpose of all that fundraising is to secure a U.S. competitive advantage in eVTOL technologies through the evolution of a profitable commercial industry, and money alone won’t build an aircraft. The availability of talented engineers is seen by industry as a major limiter to the rate of progress.

The Vertical Flight Society estimates that each eVTOL developer will need 500-1,000 engineers to bring their aircraft concept to certification. Those companies will be in competition with the helicopter industry, which is also seeking thousands of engineers in the coming decade for military and civil rotorcraft development projects, including the U.S. Army’s Future Vertical Lift procurement effort as well as other Navy and Air Force programs.

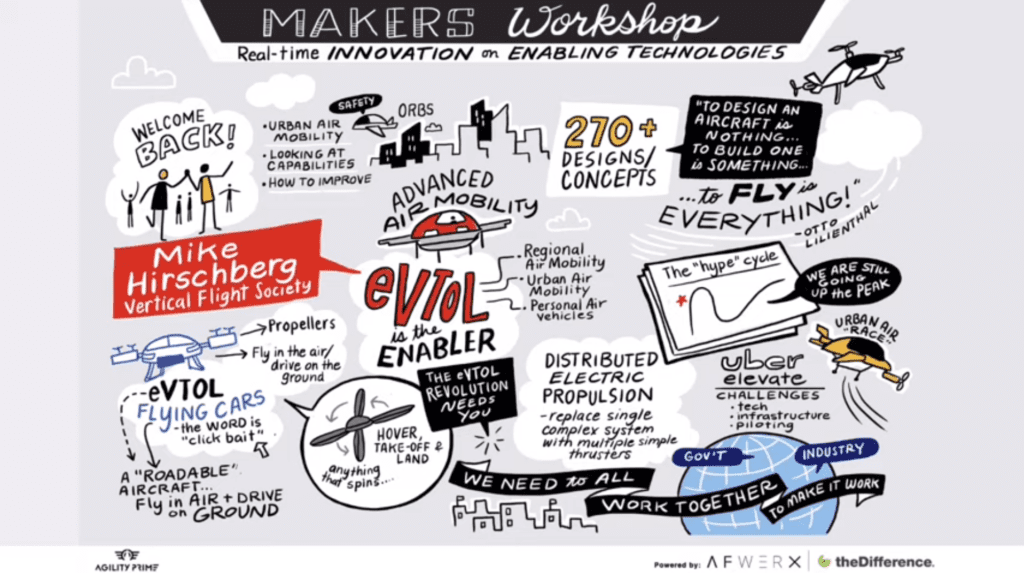

“The workforce is one of those critical bottlenecks that is going to prevent us from reaching this future that we all want, if the talent pipeline is not soon ramped up,” said Mike Hirschberg, executive director of the Vertical Flight Society. “We’re estimating we need a thousand [new] engineers a year for the next decade to meet these critical national security and economic needs.”

Government and military-funded Vertical Lift Research Centers of Excellence (VLRCOEs), established in 1982 to support academic research and training, receive less than $5 million in static annual funding from NASA and the military. A white paper released by VFS in March contends that expanding funding for the existing VLRCOEs would be one of the most effective ways to confront the talent shortage.

“We already have a lot of great infrastructure that we can use here,” said Marilyn J. Smith, director of the VLRCOE based at Georgia Institute of Technology, speaking to workforce concerns during the Agility Prime kickoff event. “Teaching vertical lift is not a traditional engineering education that you get at the mechanical, aerospace and electrical engineering schools across the country.”

Farhan Gandhi, aerospace program director for the Center for Mobility with Vertical Lift at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, advocated for three new funding efforts: an increase of $5 million per year for VLRCOEs to fund more graduate students; $1.5-2 million to hire late-career experts as adjunct professors; and an additional $5 million to fund more tenure-track faculty.

Gandhi also suggested reviving a now-defunct combined government-industry funding pot for pre-competitive research work, housed under the Vertical Lift Consortium, to advance eVTOL-related research and provide more projects for academia.

These efforts, totaling $17-18 million in annual funding, could produce up to 100 additional Masters and PhD-level graduates per year, Gandhi said — not sufficient to satisfy industry need, but these individuals could “form the linchpins” of development teams that companies build around.

Leaders in vertical lift academia also advocated for programs to expand the scope of their existing educational programs to better support eVTOL aircraft and urban air mobility, with Smith noting that the University of Maryland will introduce a graduate program in eVTOL design this year.

Carlos E. S. Cesnik, director of the active aeroelasticity and structures research lab at University of Michigan, said the current mechanically-focused curricula should take a more “systems of systems” approach to including software, operational infrastructure and other elements of modern airspace systems.

“When designing an advanced air mobility system, automation, airspace integration, human-machine interaction, cybersecurity … all of these are as important as the airframe itself,” said Cesnik. “The challenge here is that most of these contributing disciplines fall outside most of the aerospace engineering programs.”

“If innovation is a battlefield, academia is our training camp.”