Norway, one of the most progressive governments on electric aviation, is more focused on battery-electric than incremental improvement through hybrid systems.

Sustainable aviation leaders are divided on whether hybrid-electric aircraft technologies are likely to play a major role in the aviation market over the next few decades.

Speaking during a webinar hosted by the Vertical Flight Society and the CAFE Foundation, participants from both established aerospace companies and startups discussed the energy density limitations faced by battery-electric systems as well as the challenge hybrid systems face in overcoming their added weight and complexity to deliver a benefit.

Powertrain company VerdeGo Aero is exploring both hybrid- and battery-electric technology, said co-founder and CEO Eric Bartsch, who stressed there is no “one size fits all” answer and various powertrain solutions viable for different aircraft and missions. Bartsch identified efficiency, emissions, and noise as the three primary barriers to future growth in the aerospace industry.

“If we make improvements on those, that’s only useful if there are electrons in the aircraft to deliver a useful and safe mission profile,” Bartsch said. “Hybridization is really the path that allows you to make significant progress on efficiency, emissions and noise while also still having an aircraft that is highly useful and capable.”

But for a hybrid powertrain to deliver improvements in those three areas, it must overcome the added weight and complexity inherent in its design. For that reason, VerdeGo opted last year to partner with Continental Aerospace Technologies on a distributed hybrid-electric propulsion system integrating diesel piston aircraft engines, rather than turbine engines that have a poor power-to-weight ratio when scaled down.

“The things that we like about small turbines for current commercial aircraft don’t necessarily play through to the rules of hybridization,” Bartsch said. “The motivations for the diesel hybrid are basically to power the hybrid in a way that doesn’t negate the motivations for electrification.”

Eric Bartsch, CEO of VerdeGo Aero, believes we are at the beginning of an electric propulsion revolution, but the technology has yet to provide more utility than jet engines. (VerdeGo Aero)

VerdeoGo Aero says its hybrid-electric system, scalable up to 1 MW of peak power, is 40 percent cheaper to operate, emit 35 percent less CO2, and is ten decibels quieter than a turbine hybrid-electric system.

Michael Winter, senior fellow for advanced technology at Pratt & Whitney, said hybrid systems are a systems engineering problem, and picking the right architecture for the system and the mission is key.

For smaller aircraft, such as urban air mobility (UAM) or general aviation, today’s technology can enable those missions through either a turbo-electric or battery-electric approach, Winter said, but larger aircraft — from business aviation all the way up to a long-haul jet — require either a series or parallel turboelectric hybrid approach.

“Series hybrid is interesting, but in most cases — especially for a retrofit — it probably does not buy its way in. You need to add a generator, a converter, some cabling, a motor drive, a motor … all of that adds about ten percent loss of efficiency,” Winter said. “It’s a 3X increase in system weight, with today’s numbers it’s about a 2X increase in system cost … but there could be value that enables novel aircraft architectures,” such as distributed electric propulsion and blended-wing body, as well as added redundancy for safety.

Winter said he’s bullish on the parallel hybrid approach for larger aircraft, using much of the same electric propulsion hardware that enables small UAM or general aviation aircraft combined with turbines to deliver about 18 megawatts of peak power.

Though electric cars are rapidly becoming an affordable and practical low-emissions option, for many years, hybrids — led by Toyota’s Prius — offered a “bridge” solution with significantly better environmental impact than its ICE counterparts. As battery technology continues to improve, hybrids may play a similar role in aviation.

The various systems architectures available for electric and hybrid-electric aircraft. (Michael Winter / Pratt & Whitney)

Not all sustainability advocates believe a hybrid approach is worth pursuing, however.

In the Nordic region, few are talking about hybrids, viewing them as “not enough” of an answer, similar to Airbus and Rolls Royce’s public justification for ending their hybrid-electric E-Fan X pursuit.

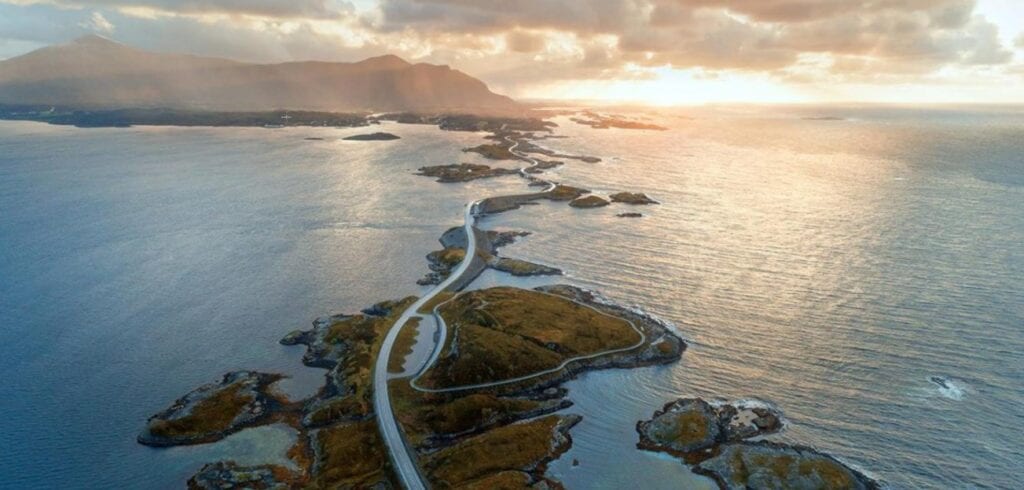

“In Norway, we have the highest sale of electric vehicles per capita than any country in the world. We are beyond the discussion about hybrid,” said Eric Lithun, CEO of Norwegian electric airline startup ElFly. “Here, we [saw] the business case with electric ferries. We have 74 electric ferries in operation now, and they’re making more money and they’re environmentally friendly. So we get [electric vehicles] for cars and for ferries, and everybody says we need it now for aviation.”

Government agencies and aerospace industry players in northern Europe formed the Nordic Network for Electric Aviation, or NEA, to accelerate the introduction of electric airplanes and lower carbon emissions. The group has given out €375,000 in grants so far to companies like ElFly, which placed an order with Bye Aerospace for 18 of its eFlyer 2 and 4 aircraft.

Västerås, Sweden-based OSM Aviation Academy, which supplies pilots to the commercial aviation industry, placed an order for 60 eFlyer 2 aircraft in 2019.

With a goal of reaching zero emissions from domestic aviation by 2040, the Norwegian government plans to waive landing fees for electric airplanes until 2025, subsidize some routes and offer free charging to help shift short-haul flights to electric. Other European governments continue to heighten their carrot-and-stick approach to sustainability in aviation, both passing mandates and offering subsidies or research and development grants for lower-carbon approaches.

How these mandates will be achieved — particularly regarding nations like Sweden, which has pledged to be zero-emissions by 2045 — may include a mix of technology, from sustainable fuels to electric airplanes and hydrogen, as well as cleaner grid power generation.

“I wouldn’t invest in a hybrid,” Lithun said. “I wouldn’t put my money there.”

VerdeoGo’s Bartsch agreed that in the long term, hybrid systems are a bridge to batteries — as battery-electric powertrains are a simpler solution — but sees substantial opportunity for hybrid aircraft until then.

“That transition phase is a lot longer than I think most people appreciate,” Bartsch said. “When we look at the current state of batteries versus hybrids, the energy density challenges are substantial. But even if those are solved, we have significant challenges with cycle life time, calendar life time, charge rate, charging infrastructure and even the cost of operations … [because] the consumable components inside a battery powertrain, being the replacement batteries, drive up the cost.”