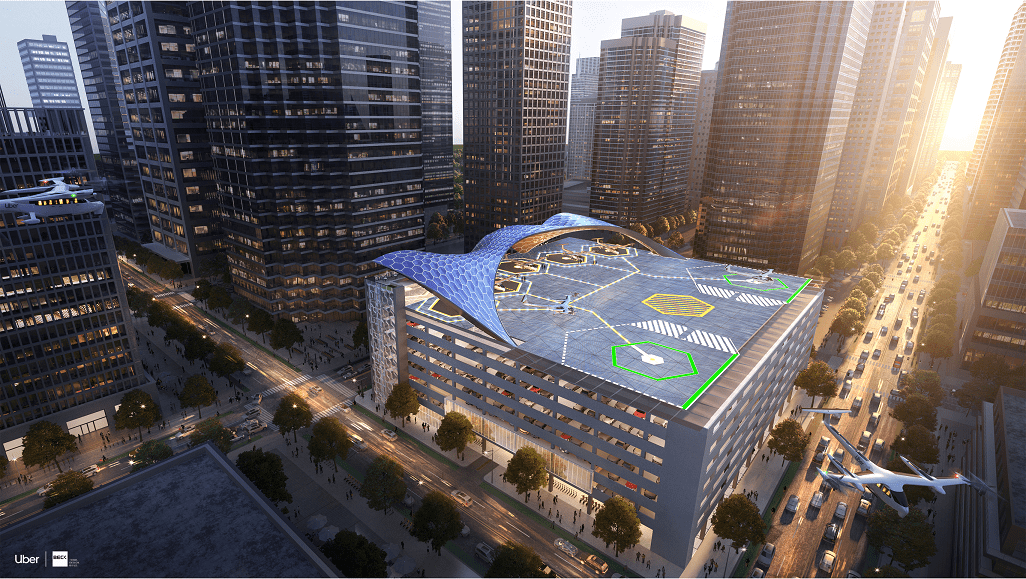

As communities discuss how to prepare for urban air mobility, it’s unclear whether the FAA will have authority over most vertiports. (The Beck Group/Uber Elevate)

Large investments have been made into the development of electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft over the past few years, however, the less flashy topic of infrastructure is often a second thought when considering the development urban air mobility (UAM) as an industry.

Last week during a panel discussion featured as part of the Vertical Flight Society’s Forum 76, Rex J. Alexander, president of Five-Alpha LLC, explored current VTOL infrastructure and how it would have to be expanded for the future of UAM.

Since Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) guidelines on UAM have not been fully established, Alexander explained current FAA regulations that currently impact in-service VTOL aircraft. FAA 14 CFR Part 77 and Part 157 establish guidelines for the safe, efficient use, and preservation of the navigable airspace and notice of construction, alteration, activation, and deactivation of airports, respectively.

“We get dimensional criteria. We get terminology. We get processes from these locations,” Alexander said. “Additional guidance that you have to pay very, very close attention to in infrastructure for heliports, and soon to be vertiports, if you’re looking to get involved in the Department of Defense in any way, shape or form you have to pay very close attention to what’s called unified facility criteria or UFC. This is where all the major services point to.”

Alexander used this information to create a white paper with Jonathan Daniel, chief of strategy at NUAIR Alliance, which Alexander presented at Forum 76.

“So, in the statistical analysis that we looked at, there are 19,669 planning facilities on record in the United States,” Alexander said. “That being said about 30% or 5,918 are on record as being heliports. The thing that we have to pay very close attention to and going forward is what we’re going to call these, so there’s currently public owned or private owned, but it’s the use case that’s the most important.”

According to Alexander’s research, there are currently only 58 public use heliports in the United States. Public use heliports refer to locations where anyone with the proper licensing certification can land, opposed to private use which would be restricted.

“You can’t just land a private use facility unless you get permission from the individual,” Alexander said. “All hospitals in the United States are private use, and most, 99 percent, of all heliports in the United States are private use. These two cases do not encapsulate or capture what our vision is for urban air mobility in the future. So, there’s going to be a need for a new definition in this space.”

However, Robin Linebarger, the U.S. and global aerospace and defense industry leader at Deloitte, said that making all heliports public use might not be the answer.

“If I’m thinking about, you know, an urban destination that is in and around an existing city, I’ve got to look at two things,” Lineberger told Aviation Today. “I’ve got to repurpose current infrastructure for generally private use. Right now, I’m not aware of any city or urban area, where they’re building where they’re going to operate publicly owned aircraft.”

Lineberger said this would require current buildings such as parking lots of existing helipads to allow companies to build out or get access to space, but it would still be considered private.

“It’s private, not in the sense that it prevents people from being there, it’s just an ownership model,” Lineberger said. “I suspect that if there’s an existing rooftop with either a helipad or not, and it could support the weight of the aircraft and all of that, that there’ll be some type of leasing concept.”

Uber Elevate is working on design standards to build UAM infrastructure to support aircraft like Ubercopter.

“I want to say a critical thing that we’re working with our partners is on the infrastructure,” Mark Moore, engineering director of aviation at Uber Elevate, said during the Forum 76 Special Session 3: Electric VTOL Testing & Certification.

“Right now we’re working a great collaboration with the FAA, NASA and our OEM partners on coming up with an infrastructure requirements document, certainly we have a great basis with [Advisory Circular] AC 150 and the heliport design guidance from which then to make sure we account for differences that relate to fixed-wing eVTOL aircraft,” he added.

Moore said Uber is aiming to start flying its partners’ first eVTOL aircraft between 2023 and 2024.

The FAA is working to keep pace with industry by writing regulations as technology is being developed. In July, the FAA NextGen office released a Concept of Operations for UAM aircraft that focused on aircraft operating in corridors.

“Our shared challenge is really trying to balance the great ideas that are coming our way and the pace that industry wants to move with the ability to make sure that those things are implemented safely,” Wes Ryan, unmanned and pilotless aircraft technology lead at the FAA, said during his Forum 76 appearance. “And so part of our challenge is reconciling these great future plans that are being put out there, with the ability to prove the technology is safe for civil use, and that the infrastructure is ready for that. Most importantly, that we’re not disrupting the air traffic that we currently have and the success and the high safety rate that we have in commercial service.”

Ryan said the FAA was looking to move away from technical demonstrations and move towards using prototype technology in low-risk use cases. This would show the reliability for civil use while allowing the FAA to gain experience while certifying the prototype.

While the UAM concept was imagined for cities, its intended location may make finding available and affordable space a challenge.

“At the end of the day, we have to link that to the infrastructure and the cost of infrastructure,” David Solar, SC-VTOL lead at the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), said. “All of them are probably located in high-density areas where the ground cost is quite high. So, the less infrastructure you have, the better you’ll be in terms of business at the end of the day.”

Agility Prime, an Air Force program that works to accelerate the commercial market for advanced air mobility vehicles, aims to eliminate some risks for companies in the field by doing early airworthiness internal to the Air Force, Col. Nathan Diller, Afwerx Commander at the Air Force, said.

“That early airworthiness allows us then to increase revenue-generating use cases that one creates data, that ideally we can share with the civil regulators, as well as creating revenue and reducing the financial risk associated with this market,” Diller said. “And then that third piece that fights financial risk reduction is a place where as an early adopter, we in the Air Force feel that in the very near term, we planned by 2023 to begin fielding our units internally to the Air Force with these future electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicles. In doing that, you know, clearly some of the other risks we expect to touch along the way, like some of the infrastructure risks.”

Diller said the infrastructure calculations would include the positioning of charging stations and technologies that would allow many of these aircraft to operate in a dense area.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has also been working with the FAA and many companies in the industry on technology development in this area.

“We’re trying to understand the unique characteristics of the vehicle so that we can provide suggested evolutions of the existing vehicle infrastructure and airspace standards to enable this market,” Starr Ginn, urban air mobility thought leader at NASA, said. “We actually have organized flight test cards for each discipline of the FAA to not only provide those requirements, breakdowns, and metrics that they’re looking for but as we implement those fly cards in our flight test plan, and we come out with deviations. Those deviations will be considered in terms of are the deviations enough or do we need to evolve or not.”

Starr also said that besides flying vehicles, this data helps improve automated tools that already exist, which will thus improve those tools for use in UAM aircraft.