The Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report Oct. 9 that outlines needs for improvements to the way the FAA evaluates cybersecurity for commercial aircraft avionics systems. (GAO)

A new U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report identifies six key recommendations for the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) current regulation of cybersecurity requirements for commercial aircraft avionics systems.

The report calls on the agency to hire new staff, standardize its process for assessing the cyber resiliency of connected avionics systems and establish new methods for penetration testing of aircraft networks. Important findings and insights shared by GAO also show some software vulnerabilities and the potential disruption of aircraft network functioning under penetration testing that heavily complicates how the FAA can address the recommendations moving forward.

“Specifically, FAA has not assessed its oversight program to determine the priority of avionics cybersecurity risks, developed an avionics cybersecurity training program, issued guidance for independent cybersecurity testing, or included periodic testing as part of its monitoring process,” GAO said in the report.

Another key finding in the report is more guidance on independent testing to be integrated into the way the agency certifies new airplanes. GAO’s six recommendations include the following:

- Identify the “relative priority of avionics cybersecurity risks compared to other safety concerns and develop a plan to address those risks.”

- Implement new training for agency inspectors “specific to avionics cybersecurity.”

- Include independent testing in new guidance for avionics cybersecurity testing of new airplane designs

- Develop procedures for “safely conducting independent testing” of avionics cybersecurity controls in the deployed fleet

- Coordinate a tracking mechanism for ensuring avionics cybersecurity issues are resolved among “internal stakeholders.”

- Review oversight resources the agency has currently committed to avionics cybersecurity.

In the report the investigators note that the FAA concurred with five out of their six recommendations.

“The FAA believes any type of testing conducted on the in-service fleet could result in potential corruption of airplane systems, jeopardizing safety rather than detecting cybersecurity safety issues,” the report says.

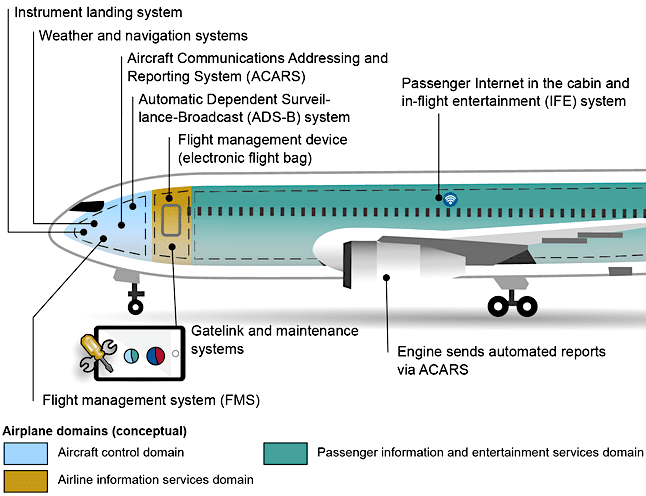

Several cyber risks to avionics systems are highlighted in the report including flight data spoofing attacks and outdated systems on legacy aircraft. Other risks include software vulnerabilities and the long update cycles that are common for in-service avionics systems. Malware or malicious software is also referenced because of its ability to be inserted into installed on an Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) application, which are increasingly becoming more connected to flight management computers.

“[Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System] ACARS transmissions are unauthenticated and, thus, could be intercepted and altered or replaced by false transmissions. For example, unprotected ACARS communications could be spoofed and manipulated to send false or erroneous messages to an airplane, such as incorrect positioning information or bogus flight plans,” the report says.

In recent years, several cybersecurity researchers have also highlighted risks and demonstrated vulnerabilities to in-flight connectivity systems at the annual BlackHat and other professional cybersecurity conferences and events. As an example, during the August 2020 BlackHat virtual presentations, an Oxford researcher presented his team’s results using some basic home television equipment to eavesdrop on satellite signals that expose in-flight passenger data.

That research also was able to view communications and data generated by a tablet EFB connected to an aircraft network used by a Chinese airline.

Avionics manufacturers have taken steps to address vulnerabilities highlighted in the report, and the FAA has collaborated with industry to develop a consensus on managing cyber risk to connected aircraft systems primarily through the use of DO-326/ED-202, an airworthiness security process specification jointly developed by RTCA (U.S.) and EUROCAE (Europe). FAA officials told GAO that they’re still developing new policy and official regulation around more consistency for the way it assesses cybersecurity of avionics systems.

Some technology suppliers have also developed new methods of monitoring and improving the cyber resiliency of connected avionics systems. CCX, a Canadian avionics manufacturer, makes a computer designed to monitor aircraft network traffic in real time.

“Our perspective is there should be perpetual monitoring of onboard networks all the time, the Ethernet-based activity and proprietary avionics data bus networks such as ARINC 429 traffic should be monitored,” Bartlett told Avionics International. “How do you know what’s going on with your aircraft’s network if you’re not actually monitoring and alerting on certain events that you have pre-established as a risk? I think there needs to be a paradigm shift that happens in the industry that at a baseline there should be active monitoring of all onboard networks.”

Airlines also expressed concerns to GAO on the ability of the FAA’s certification process to address avionics cybersecurity and disclosure of independent testing results from manufacturers. Under the current certification process, applicants typically submit a final testing plan that includes cybersecurity testing prior to entry into service. After that, airlines are required to adhere to an Aircraft Network Security Program that they submit to the FAA covering how they will maintain the aircraft’s internal networks.

The Aircraft Network Security Program also includes “a forensic analysis process to address safety-related cybersecurity incidents,” with no specification for periodic testing to reduce risk.

“In the absence of FAA guidance, representatives from one airline stated that they have formed a group with four other airlines to try to determine how to safely perform independent testing on their respective fleets,” the report says.

Third-party testing is however starting to become more standard, as the report highlighted interviews with Airbus and Boeing officials who both allowed third-party penetration testing during the development process of their most recently certified in-service aircraft types. Boeing has also established a new web-based vulnerability disclosure program where independent researchers can directly report potential new threats that they discover.

“You can establish filters, and identify the root causes of problems if you’re constantly monitoring what you consider to be a critical alert on, for example, a 429 data bus. If you have the ARINC tags identifying critical alerts, you would be able to see for example if your rate of climb changes in excess of the aircraft’s capability. When you’re constantly monitoring, you can do data forensics and understand what actually happened to cause a critical event, set alerts around that, and troubleshoot to discover the root causes of those critical events,” Bartlett said.

According to GAO, the FAA is preparing detailed responses to all but one of its recommendations: to develop a method for independently testing the in-service fleet.