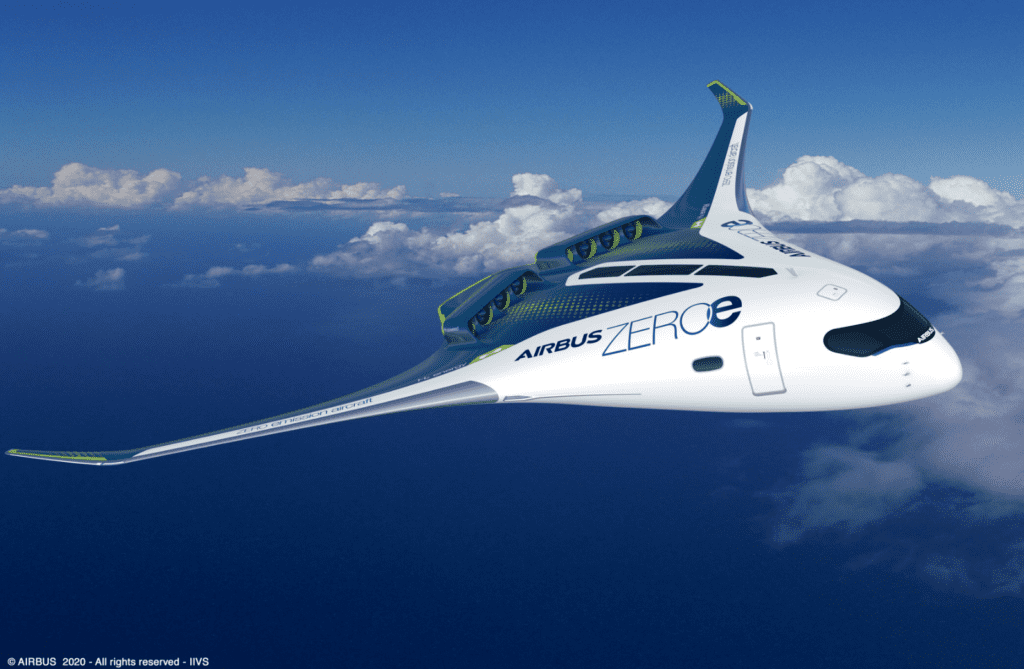

The Airbus ZEROe concept blended-wing body design is one of three concepts from Airbus for hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft. (Airbus)

There is little argument in the aviation industry about the need to create more sustainable aircraft, however, how and when to achieve zero emissions is still up for debate. During a Dec. 8 Global Symposium on the Implementation of Innovation in Aviation virtual panel hosted by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), industry professionals focused on alternative fuel sources like hydrogen, efficient air traffic management, and cooperative governing bodies as pathways to zero emissions aircraft.

“Business as usual will not get us to decarbonization path required science and by society,” Jane Hupe, deputy director of environment at ICAO, said in a taped address. “Aircraft today is 70 percent more quiet and 80 percent more fuel-efficient than in the 1960s, showcasing how the aviation sector has undergone spectacular innovation over time. But the fundamentals have stayed the same.”

This constant evolution of the existing technologies will continue to be needed, but only the introduction of radical disruptive revolutionary innovation will be able to deliver the inspiring levels of decarbonization required in order to respond to the evolving consumer demands and regulations, according to Hupe. “Long term commitments are essential for the construct of decarbonization pathways but should not shadow the need to act now,” she said.

A key to lowering emissions is finding alternative fuel sources. SkyNRG, a global leader for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), has been working on this aspect of the zero-emissions equation for 10 years. Their mission is to make SAF the new global standard, Charlotte Hardenbol, head of programs and solutions at SkyNRG, said during the panel.

SkyNRG started by increasing small demonstration-scale projects and now has continuous volumes being produced daily, Hardenbol said. However, the production quantities they are hitting now will need to be increased by at least 85 percent to meet ICAO’s 2050 targets.

“To actually reach our global climate targets, we need to build production capacity for SAF fast,” Hardenbol said. “If you look at the ICAO 2050 targets for a 50 percent carbon reduction versus 2005, for instance, that would mean that we would need to produce around 265 million tons of SAF by 2050. To give you a sense of perspective, we’re around 100, maybe 200,000 tons in 2019. So, for us to reach that, we would need to build 500 sustainable aviation fuel production facilities at a scale of 500,000 tons until 2050. And that will need a lot of innovation for new technologies to scale and a lot of funding.”

Companies like Airbus and ZeroAvia are looking to hydrogen as a clean alternative fuel source. Simone Rauer, head of aviation environmental roadmap for corporate affairs at Airbus, said hydrogen is the most promising alternative fuel source because it is produced from renewable energy and other countries are also interested in investing in it.

In September, Airbus unveiled its ZEROe zero-emission commercial aircraft concepts. Rauer said Airbus is exploring technologies like hydrogen fuel cells, hydrogen combustion, modified gas turbine engines, and cryogenic storage of hydrogen insulated tanks for these concepts. In the next four to five years, Airbus will have technology demonstrators and in 2025 they will make a decision about what sources of power to pursue with a focus on developing a full-scale prototype in the late 2020s.

“While we’re focusing really on CO2 emissions for this whole holistic decarbonization approach, as a priority, we do not forget about the reduction of other emissions and environmental aspects of the lifecycle of an aircraft,” Rauer said. “This is also the case for hydrogen technologies by, for example, considering their CO2 reduction potential all along the lifecycle.”

ZeroAvia has completed a “world first,” with a hydrogen fuel cell powered flight of a commercial-grade aircraft. (ZeroAvia)

ZeroAvia already completed a test flight of its hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft this September. Val Miftakhov, CEO of ZeroAvia, said they will have their first commercial offering of the aircraft in 2023 which will feature 10-20 seats with a 500-mile range.

“We use hydrogen as the primary fuel to propel the aircraft, but we do not burn it in the engines, instead, we convert it to electricity using hydrogen fuel cells and then use that electricity to run the electric motors that in turn, turn the propulsor,” Miftakhov said. “In our first aircraft that we’re putting on the market, this will be propellers and then we move to the larger engine or blade driving fans.”

ZeroAvia also produces the infrastructure for the hydrogen fueling process. Miftakhov said this part is essential because the majority of hydrogen today is produced by fossil fuel sources which would defeat the purpose of building a zero-emissions aircraft. ZeroAvia has built fueling infrastructure at Cranfield University in the UK that is 50 percent renewable and hopes to make it 100 percent renewable.

While zero-emissions aircraft and SAF are the ultimate goals for CO2 reduction, these are long term projects that will take years to fully implement. Benjamin Binet, vice president of strategy of airspace mobility solutions at Thales, said the aviation industry needs to also focus on what they can do now to lower emissions.

“Why do we need to act now, now as in December 2020? It’s because if we want to reach those targets long term, we need to do things as early as 2021,” Binet said. “I mean those low carbon aircraft are fantastic, but once again, we’re talking 2035…so we need to find optimization before.”

Thales has launched a green aviation innovation initiative to decrease emissions by 10 percent by 2023. Binet said one way to do this is to create a continuous improvement cycle consisting of evaluation, experimentation, exploration, and large-scale deployment of new technologies. An important aspect of this would be a “smart green meter” which would help create transparency across the industry and with customers about the environmental footprints of each actor.

Thales is also looking at optimization with operations like different routes or procedures that can have a direct impact on climate.

“What we want to do here is we want to define the procedures and invent the tools in order to have a direct impact on climate,” Binet said. “So how do we do that? …What we do is we sit together with the people in charge, so the people acting, the users. We sit with the pilot, air operations, and traffic controllers, we look at the current procedures, we invent together, we write together the operations, how we could optimize the operations in terms of the climate impact.”

However, to fully meet ICAO’s 2050 goals, a few companies cannot be acting alone. There needs to be collaborative bodies to guide initiatives, which is why the UK Jet Zero Council was created. The UK Jet Zero Council brings together senior-level representation in the government, industry, and academia to provide advice on the government’s ambitions for clean aviation.

“In 2018, the UK became the first developed country to commit to reaching net zero emissions by 2050, and whilst that’s the kind of great things for the UK is kind of credentials around climate change, it’s a challenge for me and my team because most of the modeling suggests that the aviation sector will be the highest residual is for carbon by 2050,” Darryl Abelscroft, head of aviation decarbonization strategy for the UK government’s Department of Transportation, said during the webinar.

While COVID-19 has had devastating impacts on the commercial aviation industry, Abelscroft said it presents an opportunity to innovate with new technologies while understanding the needs of the sector in the coming years.

“The focus in the UK at the moment is on restarting and recovery of the aviation sector but that does present an opportunity,” Abelscroft said. “That partnership working allows us to put a real emphasis on understanding where the sector needs to get to by 2030, 2040, 2050, but to get there we need innovation, we need the real new technologies that can cut carbon out of the sector. Many other sectors that are trying to decarbonize have the technologies already it’s about delivering but that’s not the case here. We need to collaborate and accelerate innovation if we’re going to deliver so we can achieve where we need to get to.”

Abelscroft said achieving net zero emissions by 2050 will be a prize not only for the environment but also for the economies of countries who lead the way with these technologies.