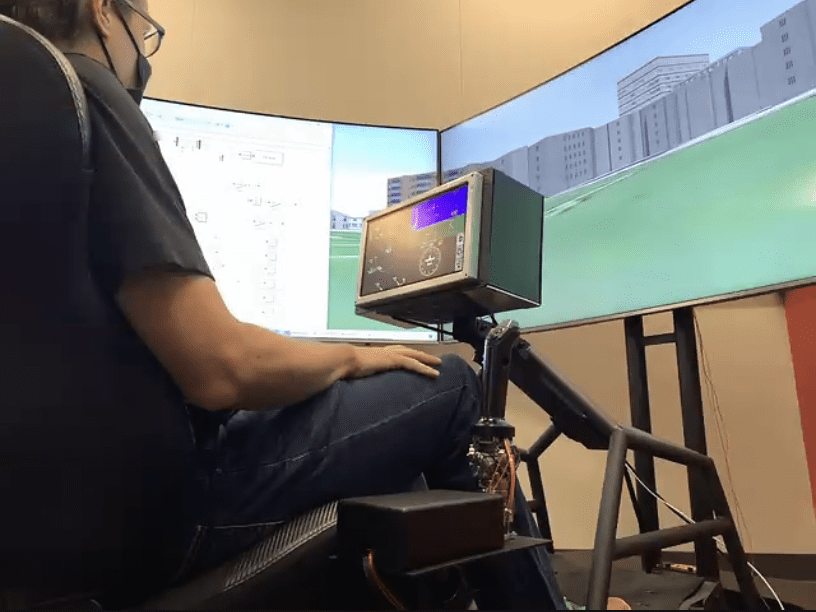

Honeywell has created a simulation environment to develop flight control computers, flight control laws, control sticks, and software for these aircraft. (screenshot was taken during a virtual tour of Honeywell’s UAM Lab)

While some companies are investing in creating urban air mobility (UAM) aircraft, Honeywell is looking towards technologies like radar, fuel cells, and flight simulators to mitigate gating factors to the industry. Honeywell presented some of these technologies in a tour of their UAM Lab during an April 21 virtual call with reporters.

“In order to make this reality happen where you have urban air taxis ubiquitous in our airspace that are flying people over the traffic, where you have cargo UAV’s that are delivering small cargo from point to point again flying over the traffic, and small drones that are delivering things like medical supplies or the order you just made from fast food directly to your house, in order for all this to become true, there are various enabling technologies that have to be researched developed commercialized and brought to market,” Stephane Fymat, VP and general manager of UAS and UAM business unit, said during the tour. “That where that is where Honeywell is focused.

One of the technologies Honeywell is working on in its UAM Lab is using radar to give drones the ability to fly beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS).

“If you wanted this drone to go further than the line of sight of the operator, this drone would need to be able to see for itself,” Fymat said. “It would need to be able to see other aircraft, other drones, high tension wires, and other obstacles and avoid them so as to not create accidents. So, in order to make the drone able to do that, it needs a set of eyes.”

The RDR 84K uses a digitally active phased array which allows the radar to be “steered” and detect objects in the airspace or on the ground. (screenshot was taken during a virtual tour of Honeywell’s UAM Lab)

Honeywell is calling this radar technology RDR 84K. It is about the size of a large smartphone and they are working to get it to weigh under a pound with the whole system weighing under two pounds. The RDR 84K uses a digitally active phased array which allows the radar to be “steered” and detect objects in the airspace or on the ground, Hector Garcia, senior director of engineering at the UAS and UAM business unit, said.

“It is a digitally active phased array,” Garcia said. “What that means is that we’re able to actually steer the radar to be able to detect anything in the air or on the ground. We are developing a multipurpose radar to help us for avoidance of cooperative and noncooperative threats that may appear in our pathway.”

To be able to use the radar to detect and avoid objects in the airspace or on the ground, Honeywell is developing algorithms for the system, Garcia said.

The RDR 84K radar can also be used as a GPS, Garcia said. It uses its radar as an altimeter and is able to map the terrain and then compare it to Honeywell’s databases.

“We also have equipment at Honeywell that we’ll be able to use in the GPS denied environments or where the GPS is lost,” Garcia said. “We have our inertial units that will be able to tell the drone exactly where it is in case the GPS is lost.”

A draw of many UAM vehicles is their use of electricity however current battery solutions often do not provide extended ranges and require downtime after flights to charge. Honeywell’s UAM Lab is working on a hydrogen fuel cell as a solution to this problem.

“Instead of having batteries on top, it has a hydrogen fuel cell system,” Fymat said. “What this fuel cell system does is it takes hydrogen, combines it with oxygen to produce electricity to power the propellers.”

Honeywell’s UAM Lab is working on a hydrogen fuel cell as an alternative to batteries (screenshot taken during a virtual tour of Honeywell’s UAM Lab)

The fuel cell Fymat and Garcia presented was made for a drone and proves triple the amount of use time and takes about 10 minutes to recharge instead of two hours. Garcia said this technology was created in a partnership with BFD Drone Technologies.

For larger UAM operations such as air taxis, Honeywell has created a simulation environment to develop flight control computers, flight control laws, control sticks, and software for these aircraft.

“What we’re showing you in this lab is a whole simulation environment that is used by our engineers and our test pilots in order to develop the flight control computers, flight control laws, control sticks, and all of the software that governs how future air taxis will be piloted and how they will fly,” Fymat said. “The emphasis of today has been primarily on the algorithms and how the vehicle will fly, the fact that if you try and roll a vehicle and turn upside down, the software prevents that.”

The simulator uses Honeywell’s next-generation avionics system which uses a distributed processing module (DPM). (screenshot was taken during a virtual tour of Honeywell’s UAM Lab)

The simulator uses Honeywell’s next-generation avionics system which uses a distributed processing module (DPM), Garcia said. The DPM is open architecture so it can be modified for the complexity of the vehicle.

“The purpose of our lab is to be able to replicate, reproduce, and help integrate with our customers,” Garcia said. “We will have the actual equipment here in the lab that is representative to the avionics onboard for vehicles. We’re able to integrate, troubleshoot, help them develop test loads, and work with our fly-by-wire system.”

The flight control computer operates the simulator, Garcia said. During the presentation, a pilot deviated from the flight plan which was loaded into the simulator.

“This will enable a fly by wire system is always in total control,” Garcia said. “We’re going to show you here very simply, Andrew [the simulator pilot], is going to go ahead and deviate from the flight path…and now the pilot is actually in control. I’m going to have Andrew do a very serious turnover bank, and…he is moving as far right and left as possible. The fly-by-wire system is preventing any unsafe attitude situation. Once he lets go of the inceptor, two things happen: the vehicle levels and will actually go back to the flight plan.”

This software system provides a simplified form of vehicle operations. Making these vehicles easier to fly will also help solve another problem in the aviation industry: pilot shortages.

“In order to make the vision of these urban air taxis come true when you have many of them flying, we’re going to need a lot of new pilots,” Fymat said. A lot of new pilots have to get ramped up quickly, in order for this industry to grow. What that means is that we have to make it more and more simple for these plants to learn how to fly these vehicles because the simpler it is to learn how to fly, the quicker they can become proficient, the less recurring training they need, and the more quickly the industry grows.”

The simulator and simplified vehicle operators also advance the use of autonomy in aircraft, Fymat said. For air taxis or manned aircraft, this will be a progressive evolution.

“Our view is that autonomy will be a progressive evolution,” Fymat said. “What we showed you today was a simulation of a pilot sitting in an aircraft with a simplified form of operation. A lot of the complexity was automated so that the pilot didn’t have to do as much to aviate or fly the vehicle. More and more can be done to further automate a lot of the tasks that today are done manually by the pilot. The further you automate those tasks, and you simplify what the cockpit displays look like you are progressively going down the road towards autonomy.”

Fymat said that Honeywell’s technology is on track to meet the 2024 deadline that some UAM companies are targeting for the rollout of their aircraft.

“We believe it is an accurate but aggressive timeline,” Fymat said. “A lot can happen in development and flight test programs, so if things go according to plan, I believe that 2024 is a very realistic day. If you know things come up and it takes a little longer, maybe it takes another year or two, we’re in that timeframe.”

Honeywell is already publicly partnering with Vertical Aerospace and Pipistrel, while actively working with other companies in the industry as well, Fymat said.

“Quite bluntly and simply, we see this as a very large opportunity,” Fymat said. “There’s a potential demand of $120 billion per year by 2030. That’s a very large opportunity and at Honeywell, we see that we can create a lot of value here and grow our business in this segment. We also see this as a very disruptive part of the market.”