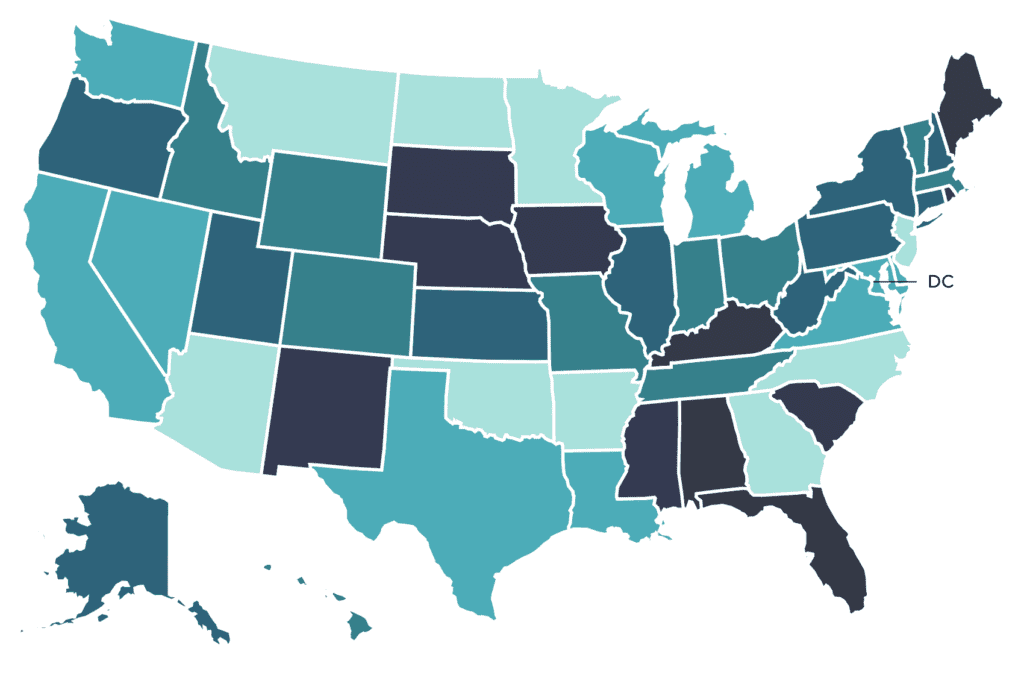

A new research report recommends creating drone corridors to enable advancements and growth of the commercial drone industry. The report also features a scorecard that ranks each state’s “drone readiness” based on multiple factors. (Photo courtesy of the Mercatus Center, George Mason University)

New research from George Mason University’s Mercatus Center indicates the need for states to create and manage drone routes in order to enable growth of the commercial drone industry in the U.S. The research paper, authored by senior research fellow Brent Skorup, also features a ranking system that compares the “drone readiness” of each state. Oklahoma ranks as the most prepared for commercial drone services, followed by North Dakota, Arkansas, Arizona, and Minnesota. Three states tied for last place as the least prepared to enable urban air mobility: Nebraska, Rhode Island, and Mississippi.

Skorup’s ranking of states’ preparedness for commercial drone services includes six factors: airspace lease law, avigation easement law, task force or program office, law vesting landowners with air rights, sandbox availability, and jobs estimates.

The drone industry needs to work with local regulators and landowners in a way that the conventional aviation industry hasn’t had to, Skorup explained in an interview with Avionics International. While noise concerns have existed for a long time, with conventional aircraft these concerns are only an issue for residents living next to an airport or heliport. In contrast, unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) fly at low altitudes and could be targeted by trespassing or nuisance lawsuits.

Skorup had the idea that enabling drones to fly above public roadways would eliminate most of these issues. “Roadways are already dedicated for transportation; they’re fairly noisy and handle a lot of logistics,” he said. “Establishing drone corridors above public roadways at low altitudes is a fairly simple and elegant way to open up millions of miles of these corridors.”

One of the few sites in the U.S. where the FAA currently allows test flights for drones is the 50-mile drone corridor in New York. NUAIR, a nonprofit that manages operations at the New York UAS Test Site, received FAA authorization for drone operations beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) for 35 miles of airspace within the corridor.

The report published by the Mercatus Center demonstrates the importance of allowing use of airspace over public roadways to make drone flights more feasible. Skorup also sees avigation easements as a priority. Avigation easement laws enable drones to fly as long as they are at an altitude high enough to not disturb people on the ground.

Skorup’s research includes the suggestion that establishing many more designated places for testing new drone technologies would allow companies to more effectively demonstrate their products to regulators and investors. These places, referred to as sandboxes, could be underused airports or rural airspace. “It’s important in this industry to show proof of concept, and have something to show investors and regulators—not just business plans,” he remarked. Developers of drones, electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft, and UTMs (UAS Traffic Management) could all benefit from dedicated public facilities for testing.

Even though drone technology is fairly advanced, Skorup said, it’s difficult for companies to make a business case while depending on one-off waivers from the Federal Aviation Administration. There are a lot of pilot programs in the U.S. for drones, such as Zipline’s, he noted. Zipline recently received its Part 135 Air Carrier Certificate from the FAA, and has been performing drone flights in Arkansas under the FAA’s Part 107 rule since last year.

“A lot of companies in the past year or two have really struggled. They need access to airspace,” Skorup stated. He recommends that the FAA and state departments of transportation coordinate in whitelisting low-altitude airspace—below 200 or 400 feet—for drone companies to begin routine flights and testing. He also sees a need for allowing private property owners or cities to negotiate with drone companies to get drone corridors up and running.

He also hopes to see more sandboxes open up for tests and demonstrations. Each sandbox may have different priorities; “a drone company that wants to operate in Manhattan is going to look very different than one [designed for agricultural applications] in Texas or Oklahoma,” he said.

Brent Skorup used six factors to score and rank each of the 50 states regarding their preparedness for commercial drone services. (Photo: Brent Skorup / Mercatus Center)

In spite of the challenges that drone companies and regulators are facing, Skorup believes that the regulatory framework for drone operations in the U.S. compares favorably to those in other countries. “From what I can tell, most countries and national regulators are looking to the US for leadership, and follow closely what happens here,” he commented.

China is one country that appears to be further along in the cargo and passenger drone industries. Earlier this year, Brent Skorup and colleague Will Gu wrote a report comparing drone policy and industrial policy in the U.S. and China, and also offered recommendations for lawmakers in the U.S. “Chinese regulators perceive their nation as lagging the United States and Europe in traditional commercial aviation,” according to the report. “That perception seems to serve as a motivation to leapfrog the West and lead the globe in developing commercial drone, eVTOL, and urban air mobility (UAM) standards and services.”

Skorup and Gu’s research also showed that drone regulations in China “preserve significantly more discretion for national regulators (and uncertainty for industry),” while the regulatory environment in the U.S. is at a disadvantage due to “a system of ad hoc and temporary waivers for long-distance drone operations.” However, they noted, “U.S. regulators appear prepared to apply more rigorous and general policies in the near future.”

In general, things are moving extremely slowly for the commercial drone industry in the U.S. “The FAA has a lot on its plate,” Skorup told Avionics. “It manages traditional air traffic in the U.S. amongst a lot of other things. I see drones falling through the cracks: it doesn’t seem to be a priority for the agency.” He is optimistic that more airspace can be opened up for drone operations if regulators enable local authorities to whitelist low-altitude airspace and to establish drone corridors over public roadways.