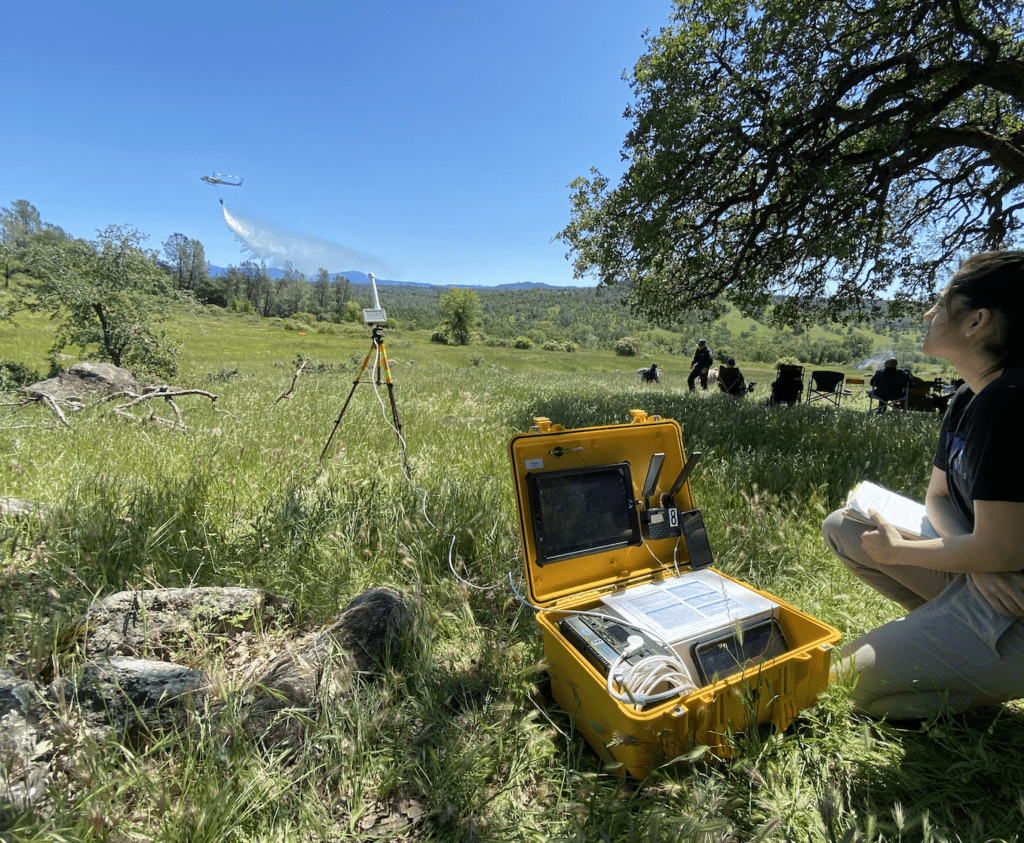

A project led by NASA’s Ames Research Center commenced field-testing of a kit prototype for drone pilots. The technology is intended to support scaling up of drone use for responding to disasters like wildfires. (Photo provided by NASA)

NASA’s STEReO (Scalable Traffic Management for Emergency Response Operations) project, led by the Ames Research Center, has developed a prototype of a drone pilot’s kit intended to help scale up the use of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) for disaster response applications. The prototype technology is designed to increase awareness of other aircraft for drone pilots by notifying them of the position of any crewed aircraft. This UAS pilot’s kit, or UASP-kit, makes it easier for the pilot to perform safe fire response operations.

In March, NASA’s STEReO team trained members of the U.S. Forest Service in using the UASP-kits, then observed firefighters as they conducted prescribed burns in national forests in the southern U.S. The Forest Service uses drones to start these intentional fires for strategic land management. The prescribed burns result in less available vegetation for unintentional fires to burn. These field tests lasted for two weeks, and the researchers from NASA gathered useful data from the fire-response professionals following the use of the UASP-kits in a real-world setting.

Using drones to fight fires is not a new concept. In 2019, drones were an integral part of minimizing the damage caused by the fire that broke out at the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. The firefighters used two camera-equipped DJI drones to most effectively direct their firehoses.

Another of NASA’s UASP-kit field tests took place in Redding, California, in May this year. NASA researchers participated in an aerial firefighting training course, led by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE). CAL FIRE has one of the largest firefighting air fleets in the worldWhile trainees learned to direct numerous aircraft operating over a simulated fire, the STEReO team tested out some of the new features of the UASP-kit.

Research psychologist Joey Mercer, who is the principal investigator on NASA’s STEReO project, spoke with Avionics International about the field tests conducted this spring. Mercer has a background in human factors and a strong interest in the decision-making process of drone operators. He explained that the purpose of these field tests is to explore the advantages that capabilities developed by NASA can provide to firefighters. “There’s no intent to automate something, or replace humans in their roles,” he said. “These are the world’s experts on fighting fires.”

The UASP-kit, Mercer remarked, functions to locally source information to enhance awareness for the UAS operator. Pilots conducting UAS missions “understand that they are the ones that shoulder that burden for see-and-avoid,” he said, rather than pilots of larger aircraft having the responsibility of avoiding any small drones.

“We were able to see right away if a new feature was working well, or if it needed immediate attention from our team’s software engineers,” said Joey Mercer, research psychologist with NASA’s Ames Research Center. “This rapid prototyping approach, when validated in these operational settings, is the fastest way for us to be sure we’re giving these users the capabilities they need.” (Photo: NASA)

A drone pilot or flight crew can use manual methods to detect other aircraft operating near the UAS. For example, visual observers can be positioned in multiple locations. They can also include an extra member of the flight crew that is responsible for noticing any other aircraft and alerting the operator. “The UASP-kit is meant to supplement their procedures,” Mercer remarked. They can still carry out all of their processes in the same way, he said, “but now we have this extra digital visual observer who can essentially tap us on the shoulder. This notion is what we’re calling technology-enhanced situational awareness.”

Mercer described a solution for UAS operators where information gathered from aircraft broadcasting their positions via radio signals is translated onto a map-like display. The operators can interact with that display to define their UAS mission’s operating area.

“We could go one step further and set up alerting rings,” he said, such as: “Please beep at me if something gets closer than X, or double beep at me if it gets closer than Y.” This eliminates the need for a member of the flight crew to be completely responsible for monitoring other aircraft. “That sort of workflow is what is supplementing that kind of proactive see-and-avoid,” he added.

One challenge is that the technology powering the antenna detecting other aircraft’s positions is dependent on line-of-sight, and can’t see something behind a ridgeline, for example. Mercer explained that there are some blind spots in the “view shed” of what the antenna can pick up, but that this challenge is surmountable.

“We’re already working to establish satellite nodes—sort of secondary nodes of these antennas,” he said. They could leave an antenna on top of the ridge which communicates with the antenna on the UASP-kit to increase visibility.

The STEReO team’s primary focus is refining the technology’s capabilities in a way that ensures safety and enables operators to do more while using the UASP-kit.

Firefighters use drones to fly into places that are considered too dangerous for conventional aircraft. Drones can help firefighters on the ground by detecting where a fire is growing fastest. (Photo: National Geographic)

Four of these kits are currently being used for real-world fire management; CAL FIRE is using one of the UASP-kits, Mercer noted. All of the feedback gathered from users will be used to improve future iterations of the UASP-kit, like making the operator’s workflow easier via the interface, or enabling more efficient decision-making.

A UAS services provider, Precision, operates aircraft for mapping wildfires and emergency response missions, most recently in support of the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of the Interior in New Mexico and Arizona. Their team can deploy UAS within 48 hours and is not limited to performing operations only during the day or when visibility is high.