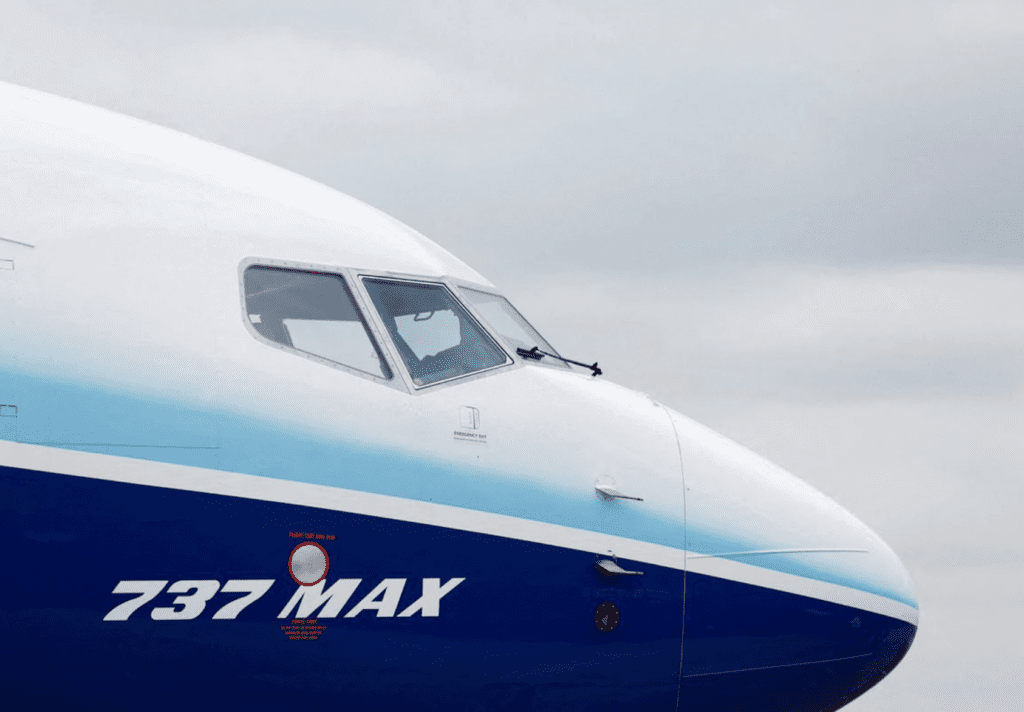

“Even if Congress doesn’t force U.S. airlines to retrofit two new safety upgrades in their Boeing 737 MAX fleets, Europe’s aviation regulator intends to ensure those enhancements are mandated for carriers there,” wrote Dominic Gates for the Seattle Times. (Photo: REUTERS/Peter Cziborra)

There is perhaps no aircraft more scrutinized in modern aviation than the Boeing 737 MAX. The aircraft, which is the fourth generation of the 737 family, offers increased fuel efficiency and a better passenger experience compared to earlier versions. Improvements like this caused it to become an instant commercial success, with massive carriers like Southwest, Ryanair, United, and American ordering hundreds of the jets to replace older aircraft in their fleets.

However, following two tragic crashes in both Indonesia (LionAir) and Ethiopia (Ethiopian Airlines), the 737 MAX was grounded for over two years as regulators discovered fundamental flaws in the aircraft. These flaws mainly surrounded the angle-of-attack sensor, an aircraft part that measures the angle between oncoming air and the wing.

Following the correction of these flaws and a $200 million settlement from Boeing, regulatory bodies across the world have since re-certified the MAX. This has led to carriers across the world, including Ethiopian, to put the 737 MAX back into commercial service. However, recent legislation has sparked another debate surrounding the aircraft model.

The controversy is centered around the Aircraft Certification, Safety and Accountability Act of 2020. This legislation requires any aircraft certified after the year of 2022 to have an improved crew-alerting system that complies with more recent safety standards. Because the Boeing 737 MAX 7 and 10 will not be certified by the year’s end, some believe that the deadline should be extended to allow these MAX variants to be certified without a newer crew-alerting system.

Some legislatures believe the deadline should be extended, but with a caveat: U.S. airlines currently operating the 737 MAX would have to make two additional retrofits to the aircraft to further ensure the safety of the aircraft. The first retrofit seeks to address the original problem with the MAX further by adding a measure that would cross-check the two existing angle-of-attack sensors through various technologies on the aircraft. The second retrofit would install a switch in the cockpit that would allow the pilot to disable the “stick shaker”—a feature that shakes the yoke of the aircraft to warn pilots of a stall. This feature was believed to have distracted the pilots in the crashes that originally grounded the MAX.

Congress is not alone in contemplating requiring the retrofits. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has indicated that it is planning on requiring these safety upgrades on all aircraft, because it was a condition in the plan to re-certify the already-flying 737 MAX 8 and MAX 9. It seems that Boeing will be forced to retrofit at least some of its aircraft regardless of the decision from Congress regarding the proposed deadline extension.

As politicians struggle to decide whether or not Boeing should get an extension to certify the 737 MAX 7 and MAX 10, it seems clear that the 737 MAX will continue to be a heavily scrutinized aircraft. With only half of the variants flying today, the road to certifying and implementing the entire MAX family could be a turbulent one for Boeing and its customers.