A NASA-funded study by Georgia Tech on regional air mobility finds untapped demand for shorter-distance flights in many under-served U.S. communities. (Photo: NASA)

Despite being on average less than 20 minutes away from a regional airport, most Americans spend time either driving to their final destination or driving to a large airport to fly on regional itineraries.

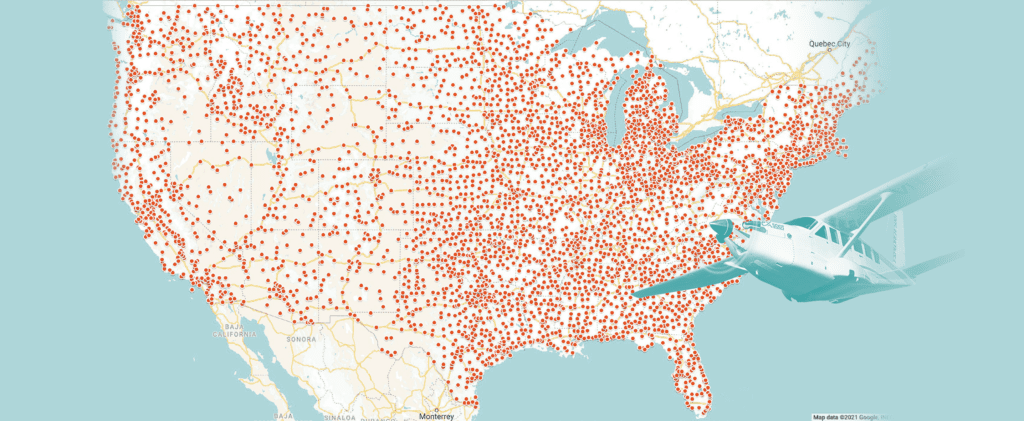

Regional airports are underutilized across the country for many reasons. Airline deregulation forced passengers to connect at about 20 hub-airports across the United States, making short flights unattractive. In parallel, airlines have retired turboprop aircraft that once efficiently connected these communities, in favor of larger regional jets that are better used on larger volume markets. Consequently, airlines no longer have the equipment to profitably serve these communities. Out of 5,000 public airports with runways exceeding 3,000 feet, only 500—just one in 10—are used by commercial air carriers.

“Regional air travel just doesn’t exist—those services have basically disappeared,” explains Cedric Justin, Ph.D., a member of the research faculty at Georgia Tech’s School of Aerospace Engineering. Consolidating flights to a few hubs has worsened aviation’s environmental footprint, creating air traffic congestion in and around large hubs, he adds.

Pictured above is Cedric Justin, Ph.D.

But advances in aviation electric propulsion systems could create a new market for regional air mobility offering additional traveling options for U.S. travelers, finds a NASA-funded Georgia Tech study.

The study identified how many long-distance travelers taking journeys greater than 100 miles would opt to fly if they had an option to fly to and from convenient regional airports near their origin or destination.

“In each region of the United States that we have studied, we have seen significant demand for those new regional air services,” says Justin.

The Northeast Corridor, for instance, is home to over 20% of the U.S. population. However, it received commercial air services at only 80 airports. The study indicates that operating a fleet of efficient electric and hybrid-electric regional aircraft could bring profitable air services at over 140 airports, connecting many more communities to the rest of the world. All told, the study identified over 4,200 Origin-destination markets connecting 980 airports nationwide with a minimum frequency of two flights per day.

Unlike eVTOL (electric vertical take-off and landing) aircraft, which take off from heliports in densely populated urban areas for very short flights within metro areas, regional air mobility services connect regions together using the network of existing airports and runways, and using fixed-wing aircraft seating between 9 and 30 passengers.

Since this new industry of regional air mobility would rely on new electric and hybrid-electric powertrains, the environmental footprint from carbon emissions or from noise is much lower than conventional aircraft. That’s of interest to NASA’s Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate (ARMD) Portfolio Analysis and Management Office (PAMO), which funded much of the Georgia Tech research.

“The results we’ve seen thus far are very promising. Dr. Justin’s work really establishes an order-of-magnitude increase in this type of transportation if it can be enabled at the costs and with the technologies that he has modeled,” says Nick Borer, Ph.D., Advanced Concepts Group lead in the Aeronautics Systems Analysis Branch at NASA Langley Research Center.

Justin is now collaborating with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, tapped to find ways to power these airports using solar-powered electricity.

“Working with the NREL, we see there are feasible changes that could be made for power delivery at these airports, especially a large increase in renewable energy that powers electrified aircraft,” continues Borer.

The first electric or hybrid-electric aircraft are expected to begin operating in the second half of this decade, with most industry experts predicting that the market won’t scale up before 2030.

“The demand is there,” concludes Justin. “Certification of these new electric vehicles and the supporting (charging) infrastructure on the ground remain the largest hurdles for the market.”