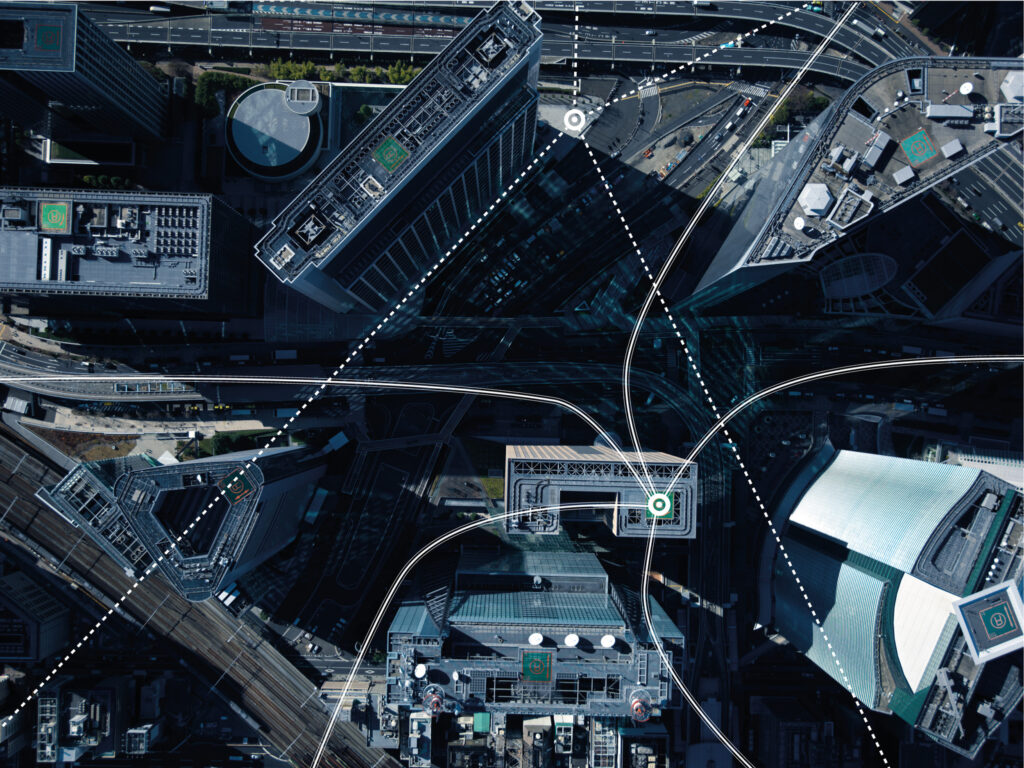

Ensuring fairness with airspace access is key to enabling uncrewed aircraft and other advanced air mobility vehicles to operate in the same ecosystem as conventional aircraft. (Photo: Airbus UTM)

Key to enabling the integration of uncrewed aircraft systems, or UAS, is establishing equitable access to airspace. Dr. Scot Campbell, Head of Airbus UTM, explained in an interview with Avionics International that they are developing the concept of a fairness engine as part of their research. Essentially, the engine will assign priority fairly to UAS operators and service providers when traffic management conflicts arise.

Airspace fairness has been a central focus for Airbus UTM since its inception. Dr. Campbell remarked that the media focuses more on early implementation of UTM (UAS traffic management) and standards, but managing fairness in the airspace needs to be a priority for the industry.

Airbus UTM has collaborated with multiple organizations to investigate airspace fairness, including Metron Aviation (acquired by Airbus in 2011) and MIT. According to Dr. Campbell, they have found throughout these collaborations that for managing uncrewed air traffic, “you can’t apply what has been done traditionally in the crewed air traffic management arena, where fairness in traditional air traffic management is largely done ‘first-come, first-served.’” The air traffic controller gives priority to the first aircraft that arrives, limiting the chance of midair collisions.

“When we started looking at the uncrewed traffic management architecture and concept, [the first-come, first-served approach] isn’t something that can be directly applied.” He explained that this is because one of the fundamental services involved in UTM is strategic deconfliction. The direct application of this approach for UTM would be “first-requested, first-served.” Someone that plans an operational intent, then, would be given first priority in the airspace.

“You can imagine a number of situations where that isn’t ideal,” Dr. Campbell said, “where you can have a lot of operators that plan in a certain area, not allowing other operators to plan in the same area. Then, there’s not necessarily a guarantee that that operator might even fly. We saw this as a big reason to really understand fairness in the UTM airspace and come up with solutions, to envision ways that fairness can be managed and controlled.”

Though the eventual goal would be to establish a service that controls airspace fairness, it’s necessary to first understand what fairness is and how it can be measured. “How can you have a system that looks at the data exchange within UTM and identifies where there might be inequities in the system?” he asks. “You have to make sure the system is recording the right metrics. That has been an early focus of our work.”

“It’s also really important that we think about this now as UTM systems are being implemented, because we want to make sure, as UTM is rolled out—even at the bleeding edge of this—that we’re monitoring and identifying fairness so that if things aren’t fair, we can do something about it.”

It’s vital to record data such as operators that did not end up flying after making a plan, those that start operating later than their scheduled time, and whether or not they fly the entire volume they had reserved. This information will provide an initial look at how the system is actually being used. “We want to have fairness across the system and to make sure that the airspace is being used as efficiently as possible, but also as equitably as possible,” Dr. Campbell explained.

In an ideal world, a system for UTM would take into consideration how frequently each operator uses a given airspace and adjusts the prioritization equitably. The system should not favor a certain type of use case over another, for example. This becomes more complex when taking into account that use cases such as package delivery or urban air mobility will not always plan operations in advance.

“The fairness engine will monitor various metrics and give priority to the operators so that we are, to the best of our ability, creating a very accessible airspace,” he said.

Dr. Campbell discussed the decentralized nature of UTM systems and the potential impact on managing fairness. “When you decentralize the system with UTM, you have a set of third-party service providers that all provide services to a different set of operators. Those third-party service providers all need to coordinate their planning so that the flights are deconflicted.”

“One third-party service provider can’t [enable] fair and equitable operations within its umbrella. It is really important, in this decentralized architecture, to have a layer that is essentially providing monitoring of fairness across the different service providers. This doesn’t have to be a centralized service; it can be a set of common rules that each of the service providers follows.”